So if liberals don’t have the tools to fight fascism, and fascism is here, what do we do? The below is hardly a comprehensive action plan – for a start we have no idea how exactly the next stage of this will shape up. We will need a hell of a lot more than this, and there are certainly other legitimate priority calls you can make. But I think these are things we all can do, right now, that may have an impact.

1. We need to realise the scale and scope of what’s going on. Charlie Stross outlines this here. There are a couple of things in there I could quibble with and a couple of things I think he’s missing but I’m not an expert on them either. Take this as a rough guide to how big and nasty this thing is. This fight is global. (Which is part of the reason I’m sitting here in the UK telling Americans what to do.)

2. I know I pointed you to Masha Gessen’s article and said institutions won’t help you. Past a certain point this is true, and we’re very close to that point in both the US and the UK. Other countries may still have a chance to stop the neoliberal erosion of democratic institutions, checks and balances, and individuals’ rights vis-a-vis the state that paved the way for what we’re seeing now.

For the US, I think there’s a couple of Hail Mary things that need to be prioritised. The one you have more control over is state legislatures. The Democrats must under no circumstances lose one because at that point the constitution is toast. I think it’s vital that some effort goes into this. The one you have less control over – but is definitely worth protesting, calling your representatives, etc. – is who Trump is going to put on the Supreme Court.

For the UK, our government has just passed the most extreme piece of surveillance legislation in a democracy ever. The companion piece to this, which would pave the way for censorship, is going through Parliament right now. It looks, for all intents and purposes, like a measure to protect children from online porn, hidden in the new Digital Economy Bill. In practice, it enables ISP blocking of websites hosting perfectly legal content. Today it’s porn. Tomorrow, it’s this blog. The day after, it’s Liberty and Amnesty International. We need to stop this.

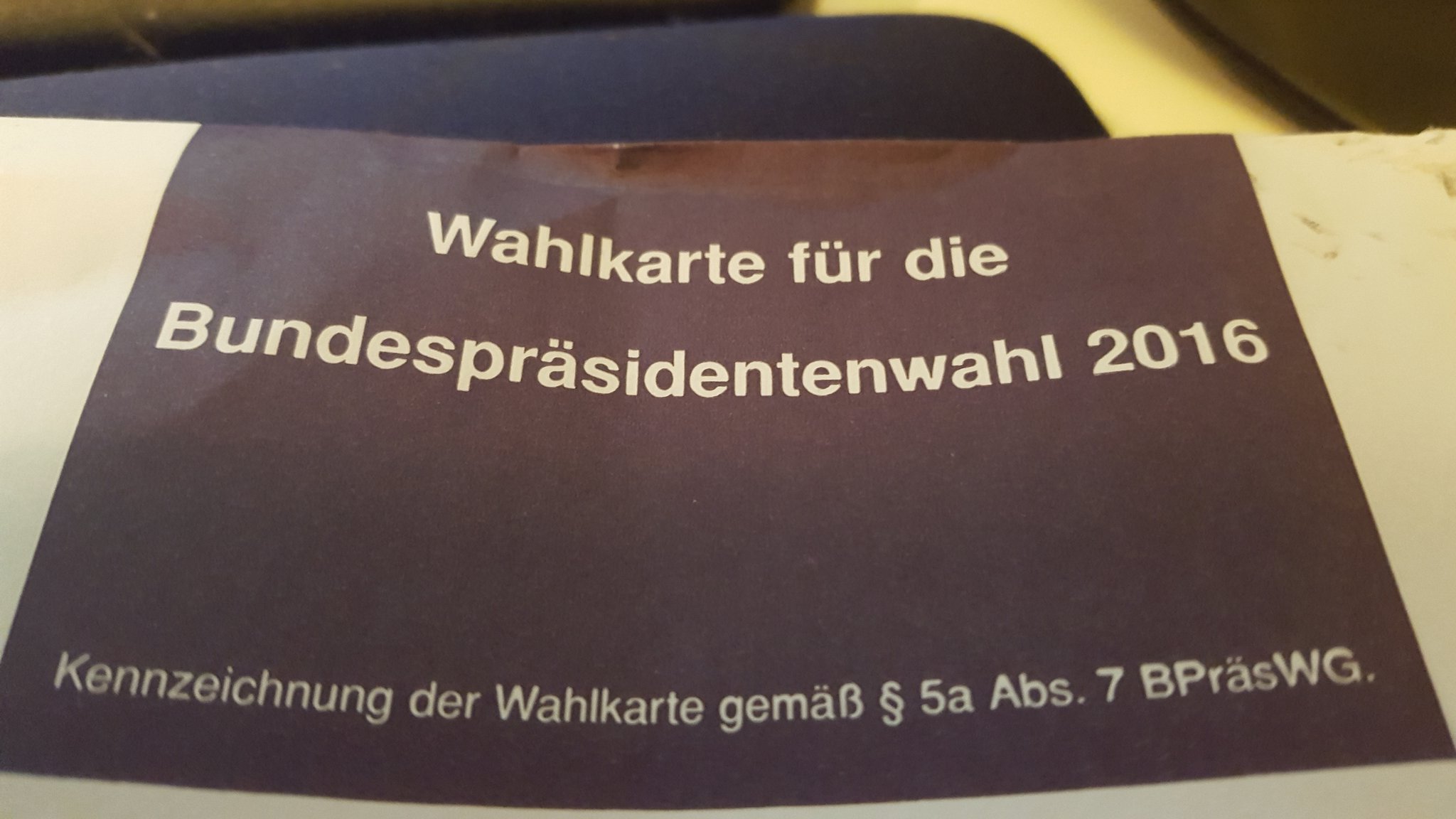

Elsewhere, fight for the independence of the judiciary; resist legislation which enables surveillance and censorship (while being aware of how power operates in both these areas and especially on issues of free speech); if you have elections coming up, get involved, campaign, vote, make sure we don’t get more Trumps out there. The ones I can see coming in the near future are the Austrian and French presidential elections, and the German parliamentary elections. (My view is extremely Eurocentric and thus flawed. There will be others, equally important, around the world.) Do not let Marine Le Pen win. Do not let Norbert Hofer win. Find a way to stop the AfD from gaining ground. Germany and France in particular must not be allowed to fall, because if they do, the European Union does. And while the EU has many flaws, in the face of global fascism we’re better off with it than without it.

3. I can’t emphasise this enough: do not normalise this. Do not let others normalise this. It’s going to make for some very uncomfortable conversations with friends and family, and I think we’re all going to lose long-lasting friendships over this, but we have got talk to people, we have got to keep naming the problem for what it is: fascism, white supremacy. Hold people to account, do not let them weasel out, do not let them tell you that “it won’t be that bad”. It already is.

4. We need to start systematically dismantling the myths of our countries that have allowed us to get to this point. In the US, that’s the American Dream, the Protestant work ethic, and the discursive coupling of “America” and “freedom”, both historically and now. Let me go into that last one in detail. It is the most white supremacist of ideas, and it is baked into the consciousness of (white) America and the world. The idea that America is synonymous with freedom crumbles at the slightest challenge even if we centre whiteness. From the House Un-American Activities Committee to Freedom Fries, these are not things a “free country” does. The minute you decentre whiteness, it becomes absurd. It’s a country built on genocide and slavery that needs to reckon with its past. But that idea of the “land of the free” (and see Colin Kaepernick on that one!) is built into the very language even “progressives” use. From Star Trek’s “space – the final frontier” to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the frontier those “aspirational” words refer to is the frontier of genocide. Genocide so normalised that organisations campaigning for human rights see no problem naming themselves after it. America is not free. Has never been free. If we do not succeed in dismantling the myth of American freedom, will never be free. Cat Valente wrote something similar here from an actual American’s perspective.

In France, it’s laïcité, among other things, which is enabling brutal Islamophobia. In Britain it’s the idea of Rule Britannia, the cheerful waving of Union Jacks every summer at the Proms, poppies, and the failure to reckon with a history of brutal colonialism and Empire, the refusal to admit that slavery is as inextricably woven into British history as it is into American history. In Austria it’s the notion that you don’t talk about politics, and the idea that once there was an Austrian empire upon which the sun never set, and the handwaving of what happened between then and now and Austria’s role in it. In Germany, it’s the false sense of security that surely we have reckoned with our past and nothing like this could ever happen here again.

Look at yourself, at your country, at what you were taught in school. Find the most cherished idea about your country, the thing you think of as part of your nation’s essence. Unpack it, take it apart, and you will see that it has been corrupted, that it serves as a tool of oppression. Question it, dismantle it, destroy it, start again.

5. On a more practical level, start sorting out an anti-surveillance infrastructure that works for you. I know it’s neither cheap nor easy and so many privacy tools are a pain to use, but trust me, the surveillance capabilities of the state are something the Trump administration, the May government, and other incarnations of global fascism are going to make extensive use of. Here’s a starting point on that front.

6. If you are a member of a marginalised group start organising, finding community, working out what other people are doing to keep themselves safe. If you are in a position to help the marginalised with time, skills, or money, listen to what they need and give it to them to the best of your ability. Do not dismiss their concerns, do not silence them.