Following on from last week’s rant about intersectionality and @pozorvlak‘s request for an explanation of solidarity “in operational terms”, I thought it might be a good time to actually write up some thoughts I’ve been having on what makes a great ally.[1] So here’s a five-ish step guide to being a great ally.

Step 0: Can I be an ally?

No matter who you are, you can always be an ally. This is not a role reserved for the ultra-privileged straight, white, middle class man. You can be the proverbial disabled black lesbian [This link will probably make you angry.], and chances are that there is still someone out there for whom things suck harder. That’s what intersectionality is all about, and ultimately that’s what solidarity and being an ally is all about.

Step 1: Check your privilege

If we accept the basic premise of intersectionality – that for some people things suck harder – and we want to do something about it, the first thing we need to do is be aware of our own privilege. This will help us understand the kind of power we have, the kind of power we don’t have, and who we can be an ally to. Being aware of your privilege is not some kind of point-scoring game that you win or lose. It’s an exercise in self-awareness, perspective, and humility.

Here’s an example. I am a member of three oppressed groups: I am female, bisexual and an immigrant. That doesn’t mean that I don’t have a whole bundle of privilege:

- I am white.

- I speak English well enough that few people can actually tell I’m an immigrant from a brief interaction.

- Even as an immigrant, I am an EU citizen so I have the automatic right to live and work in this country.

- I am in a relationship with someone of the opposite gender, so unless I deliberately out myself, I have assumed heterosexual privilege.

- I am quite disgustingly middle class, both in background and in current living standard.

- I am, as Julie Burchill would put it, “educated beyond all common sense and honesty”. (I have an MA in European Politics; some day I may want to do a PhD.)

- Though I’m an atheist, I am culturally Christian in a country that is dominated by cultural and historical Christianity.

- I am in my early thirties.

- I am (for the moment at least) able-bodied.

- I am cisgender.

Every single one of those points has a tangible impact on my day-to-day life that makes things suck less. If you want some concrete examples of how that works, the Invisible Knapsack (white privilege version, sexual orientation and gender identity version, the male privilege version) is a good place to start. It also gives me a certain amount of power and credibility with particular groups of people – it gives me a voice that someone who is not of the same group may not have.

Equally, some of these points also give me huge blind spots in my experience and view of the world. I don’t know what it’s like living as a non-white, or Muslim, or working class, or disabled person. Some areas are bigger blind spots than others. The closer I am to being under-privileged in a category, the more pre-existing knowledge and empathy I will have with people in that category. So even though I am a very privileged immigrant (see points 2 and 3 above) I have a relatively good understanding of what it might be like being a less privileged immigrant.

Checking our privilege allows us to start mapping out the “unknown unknowns” we have in our experience and world view so that we can begin to turn them at least into “known unknowns”. It’s a basic prerequisite for being an ally or showing solidarity.

Step 2: Do no harm

There are lots of ways in which we can do harm or perpetuate oppression, sometimes even with the best intentions. Probably the most common ones are denial, silencing, and dysfunctional rescuing.

Denial

A classic example of denial would be “Why do you need an LGBT group at work? Sexual orientation is not relevant to the workplace.” If you’re finding yourself questioning the validity of someone’s experience because it’s different to yours, you’re probably engaging in denial. This is harmful in several ways. Even if you only engage in denial towards the target group (say, LGBT people) themselves, you are likely to upset people and maybe even cause them to question their own experience which can be very hurtful and counterproductive. If you do this in public, you are actively using the power and platform given to you by your privilege to undermine a target group.

Silencing

“We have bigger problems – we’ll get to yours once we’ve sorted those out”; or, of course, “Transsexuals should cut it out”; or talking of “lesbians and gays” at an explicitly LGB or LGBT event. As someone more privileged you have the power to give a voice to someone else, or to silence them in all sorts of subtle and entirely unsubtle ways. Don’t do it. Just like as, say, a woman you don’t want men to speak for you or silence you, make sure you’re not speaking for or silencing others.

Dysfunctional rescuing

This one is subtle, insidious, and much like the road to hell, paved with good intentions. In a workplace LGBT context, it might be not offering the fantastic job opportunity in Saudi Arabia to the employee you know is gay, without even consulting them. The problem with this kind of “rescuing” is that, while it is indeed well-intentioned, it rarely addresses the real underlying needs of the person or group you are trying to rescue and more often than not it robs them of their own agency.

The thing about doing no harm is that you need to accept that you will get this wrong. None of us is perfect. We will commit microaggressions and sometimes macroaggressions in thought, in words or in actions sometimes on a daily basis. There are a few things you can do to minimise the harm you do with your privilege:

- Become more aware of when you might be causing harm. Think about past experiences where you think you might have got things wrong, and learn from them – don’t repeat the behaviour.

- When you do put your foot in it, and someone calls you out, don’t get defensive. Think about it, apologise, learn from the experience. Yes, this is difficult. I get it wrong all the time. Practice. If you find yourself becoming defensive, think about the “dental hygiene approach to racism” (and other -isms).

- If in doubt, shut up. For more advanced allies who may have someone they can ask, ask. But the minute you begin to doubt whether something is a good idea, put it on ice until you can validate it.

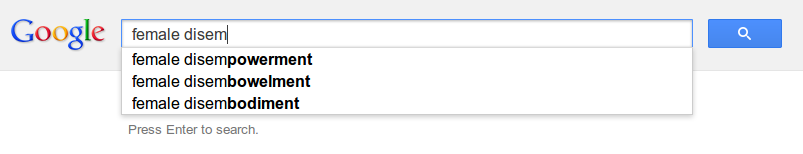

Here’s an example: I’ve been known to use the words “just because I have a uterus” as a convenient shorthand for gender discrimination. Then I started actually paying attention when trans people on Twitter kept saying “penis != man and lack of penis != woman”. Now I’m looking for a different shorthand because my previous lazy phrasing actively excludes and silences trans women and men.

Step 3: Listen!

We’ve already established that our privilege gives us blind spots in our world view, and that those blind spots can cause us to actively harm others and perpetuate oppression. So now that we have some “known unknowns” and we’re at least trying to not do harm, we can move on to turning some of our unknowns into knowns.

There are many ways to do this. If you are a novice at being an ally to a particular group, then just listening to or reading around the current discourse in the field will give you a good grasp of the key issues, the key problems, the needs of the group, the preferred language and terminology. Thanks to the magic of the internet, we live in an age where even the most marginalised groups have ways of at least talking to each other, have a little corner of the world they can call their own where they have a voice. Google will take you to it. Any type of material, from first-person accounts like microaggressions.com to academic research can give you new insights.

Asking people from the target group about their experience is also generally a good idea. However, be aware that they may not want to talk to you about it – now or ever. While I think a lot of people will be happy to answer questions if they are respectfully and sensitively framed, they are under no obligation to educate you. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t get answers the first time – sometimes it’s just not right for a person to share their experiences with an ally. That’s fine – ask someone else, ask when a better time would be, don’t give up on other ways of listening and understanding.

The act of listening and trying to understand will probably lead you to question and discard some of your assumptions – some things you thought you knew. This is a great achievement as it puts you in a position where you are less likely to do harm and more likely to be able to move on to the next step of being a great ally.

Step 4: Use your power for good

The simplest thing you can do with your power, once you have listened and understood the oppressed group, is to be the one dissenting voice among the in-group you are part of. As a straight white man, you have credibility with straight white men that a woman doesn’t. As a cis woman you have credibility with other cis women that a trans woman may not. Use that to challenge prejudice, hateful language or abusive behaviour. Call out sexism, tell your friends that rape jokes are not okay, go to Pride as an ally. Those are all great ways to show solidarity.

Having said that, sometimes it may not be the right time or place to speak out. If your actions or words may put the people you are trying to be an ally to at risk or create an unsafe space for them, then consider staying silent. Also see “Do no harm” above, and this great post on being a feminist ally.

There are other things you can do to be a great ally. The rule of thumb though is that they should always be driven by the needs of the target group. You goal as an ally is to make things suck less for them. Sometimes in the short term that may be through shutting up and not drawing attention to them, while in the long term you want to ensure that you are not part of a silent majority that tolerates or commits oppression.

The more you have listened and understood the target group, the more confident you will be in challenging oppression and doing the right thing as an ally. When I speak out against the government’s rhetoric on immigration – even when as a white, English-speaking EU citizen I technically count as a “good immigrant” – I speak both as an immigrant, but also as an ally of less privileged immigrants. Because of my own experiences, this is a topic I am very confident speaking out on. Ask me to comment on race issues, however, and I’m likely to look around for someone more qualified and point you in their direction. That’s fine too.

Some of the best allies I have worked with will go beyond speaking out. They will proactively look for opportunities to further the target group’s cause and then, in consultation with the target group, go after those opportunities. As well as accomplishing important things, this kind of behaviour can be a huge morale boost to the target group. Knowing that someone believes in you and is likely to put their personal reputation and influence on the line for you is a huge motivator. Allies like that make me work harder for my own cause as well as strive to be a better ally to others.

Step 5: Be prepared to have the difficult conversations

Every once in a while, as an ally you will be in a position where you have a better insight into how to achieve something than the target group. It may be because you have better knowledge of the privileged group, better connections, more influence. Sometimes the right thing for the target group to do may be to take a step back, to take a different approach. Those are difficult conversations to have. They can be incredibly frustrating for the target group, cause a loss of confidence or momentum. They are vitally important conversations to have, and to have respectfully and sensitively.

If you are ever in that situation, make sure that you make your commitment to the target group clear. Sometimes, from the target group point of view, it is difficult to tell whether someone is a genuine ally trying to help or just making the “right” noises while putting obstacles in your way. Make sure there is no doubt about which side you’re on, and make sure to explain why you believe a certain course of action is necessary. If you have built a trusting relationship with the target group, if they have a reason to believe in you, these conversations will be a lot easier. Ultimately, though, also be prepared for your advice to not be taken, and respect that.

As an ally, you may never get beyond step 2 of this process. That is perfectly fine and you’ll be doing a hell of a lot better than many others out there. I would encourage you to at least try step 3 – challenge your own assumptions and preconceptions; you will find it rewarding. How much you speak out and put yourself up as a target in the cause of being an ally is up to you, will vary by situation, and as long as you’ve done your homework with steps 1-3, will be greatly appreciated.

—