Welcome to Part 2 of my introductory series on feminist critiques of pop culture. In this post, I’ll cover tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle – all lazy writing techniques in which minorities and oppressed groups tend to get the raw end of the deal. I am particularly interested in how these features of our fiction and culture translate into the real world, so I’ll also discuss some of the damage they do in our day-to-day lives.

Tokenisation

Tokenisation is when you throw in a character from a minority or oppressed group in amidst all the cis, het, white, male characters. Woo hoo, aren’t you progressive! One of the many problems with token characters is that they are generally barely even sketched in. From a writing technique point of view you have to rely on tropes and stereotypes to allow the audience to fill in enough blanks to make your story hang together. What that leads to is that we see the same trope or stereotype repeated again and again until we begin to believe that people from that background (women, black people, gay people) are all like that. We get to a point where we only have a single story about a certain “type” of people.

Hogwarts is full for token characters. From Dumbledore, to the Patil twins, to a particularly badly written Cho Chang. Though I must say one of the things I love about the Harry Potter films is that Cho has this amazing Scottish accent. It’s an inspired bit of casting that adds a huge amount of depth to an incredibly flat character. It doesn’t address many of the other issues with Cho, but it does defy the viewer’s expectations and at least make you think. It offers you a different story.

Further Reading

Token Minority on TV Tropes

Some stuff I wrote about token and otherwise stereotypical bisexuals in fiction

Related trope: Black Dude Dies First

Token Gay Guy and his sidekick, Strong Black Chick

To JK Rowling, from Cho Chang

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – The Danger of a Single Story

Othering

Othering is tokenisation’s equally evil twin. Take Pacific Rim for instance. We have an ensemble cast of token characters: the Russian siblings, the Chinese triplets, the “boffins”, the black CO, the meek Japanese woman. These characters’ entire identity is that they are not “wholesome American white boy”. The Russians, despite being just as white as the lead character look profoundly different, and they barely speak. The triplets don’t even have individual names – they are simply the Wei Tang triplets. Mako, despite being raised by Stacker Pentecost from a very young age is a caricature of Western fetishisation of Japanese women, right down to the blue hair streak.

Othering is used as a device to establish distance between a character the audience is meant to identify with and everyone else, thus making the main character more sympathetic. Oh look, this one is like you, root for him. Those others aren’t, don’t worry about them. Othering allows us to forget that these people are just as human as the main character – and as us. It creates a false dichotomy between “them – the others” and “us”. We are in fact so used to thinking that any character we find sympathetic must be just like us, that we are sometimes surprised when they are not, as happened with Rue in Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series.

Othering is often a sign of lazy writing, though it is also sometimes used deliberately to make us feel sympathetic towards a character who is themselves “other” to their audience. In Guy Gavriel Kay’s Under Heaven, a novel set in a fictionalised 8th century China, the main character Shen Tai and his family are shown to have moral values closer to those of a 21st century Western audience, thus othering the rest of Chinese society. Of course the best writers can make you experience the “other” and immerse you in a culture alien to your own to the point when you begin to appreciate the intrinsic humanity. If you are white, read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart to get a sense of how that can be achieved. Manda Scott also does a good job in her Boudica series, as does Cory Doctorow in For the Win.

Othering is a common tool used in politics, and its overuse in fiction makes us all the more receptive to it. When Nick Clegg speaks of Alarm Clock Britain while Cameron and Osborne tell us about skivers, shirkers and scroungers, that’s good cop and bad cop playing a game of othering. When Gillian Duffy talks about flocking Eastern Europeans, that’s othering. When the Home Office live-tweets arrests of “immigration offenders”, that’s othering. And because we’re so conditioned to accept othering in the fictional stories we tell, we swallow it hook, line and sinker in real life too. And the extreme version of othering? That’s when soldiers call the enemy krauts, or towelheads, or terrorists – anything but admitting they are human beings, with lives and families, like you and me.

Further reading

White until proven black: Imagining race in Hunger Games

Othering 101

The Smurfette Principle

The Smurfette Principle is a form of tokenisation. Anita Sarkeesian over at Feminist Frequency does a great job of explaining it, but the short version is that when there is a single female character among an ensemble of male characters you have, for what should be obvious reasons, a Smurfette. Princess Leia? Smurfette. Uhura? Smurfette. Trinity in The Matrix? Smurfette. The interchangeable reporter in The A-Team? Smurfette.

Now whereas for minorities a certain amount tokenisation may perhaps be excused by virtue of them being, well, minorities[1], this is rather more problematic when it comes to representation of women. So if say, roughly one in ten people are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender and you have a cast of five, it’s sometimes okay to have only one LGBT character, or none at all. Women on the other hand make up just over half the human population on earth – women are not a minority. But you wouldn’t know that from the stories we tell.

What is particularly terrifying about the Smurfette Principle is how prevalent it is in real life.

In media…

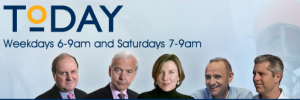

This is the presenter team of the Today Programme, Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show. Today has been on air for 56 years. For 35 of those, there have been female presenters on the programme, but for 18 of those 35 the female presenter has been a Smurfette.

This is the presenter team of the Today Programme, Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show. Today has been on air for 56 years. For 35 of those, there have been female presenters on the programme, but for 18 of those 35 the female presenter has been a Smurfette.

In politics…

You’d think things have got a bit better in the 25 or so years since that photo was taken…

You’d think things have got a bit better in the 25 or so years since that photo was taken…

And they have. There are a total of five women in David Cameron’s cabinet[2]. At this rate, it will take another 50 years to get equal representation in cabinet.

And they have. There are a total of five women in David Cameron’s cabinet[2]. At this rate, it will take another 50 years to get equal representation in cabinet.

In business…

This is the board of directors of Vodafone in 2010. Yep, that’s a Smurfette you see there. Vodafone have acquired another female director since, but I’ll let you do the maths…

This is the board of directors of Vodafone in 2010. Yep, that’s a Smurfette you see there. Vodafone have acquired another female director since, but I’ll let you do the maths…

Remember: Our stories tell us how the world is, but also how the wolrd should be. And right now they’re telling us that Smurfettes are the thing to be! But there’s only so many of us who can be the token woman in an epic fantasy adventure. What do the rest of us do?

Further reading

The Smurfette Principle on the Feminist Frequency

The Smurfette Principle on TV Tropes

In Part 3 I will (probably) talk about agency, objectification and disempowerment.

Part 1

Part 3

Series Index

Ruining your enjoyment of pop culture – Part 2

Leave a reply