Welcome back to my meandering series on feminist critques of pop culture. In Part 1 we looked at some very crude tests to see if a work of fiction contained any even vaguely realistic female characters at all and were perhaps surprised by how much of our current cultural output fails these basic tests.

In Part 2, we looked at some common, and generally sloppy, writing techniques which serve to marginalise female and minority characters in fiction.

Today, I want to talk about how women are allowed to act in fiction. I’ll cover three concepts that are deeply interconnected: Objectification, agency and disempowerment.

Spoilers ahead for: Sandman (Brief Lives in particular), Firefly/Serenity, Doctor Who (the Donna season), Casino Royale.

Women as objects

In grammar, the subject of a sentence is the one who acts, the object the one being acted upon. So in the sentence “Jill threw the ball”, Jill is the subject, and the ball is the object. The objectification of women is one of the most prevalent phenomena in our popular culture today. If you think back to the Sexy Lamp Test for a moment, you’ll realise that objectification is precisely what it tests for. In many works of fiction, even the few female characters that are around often don’t act of their own free will but are acted upon instead.

Let’s take River Tam in Firefly as an example. The first time we meet River, she is quite literally delivered in a box. To make matters worse, she spends most of the first episode being naked and afraid, presumably for someone’s viewing pleasure. Throughout the series and in Serenity, River is repeatedly silenced, wheeled around in boxes and chairs, and generally prevented from doing anything of her own accord. At the start of Serenity, we see Simon and Mal arguing over whether River should join the crew on a bank robbery. River’s own will is never taken into account in this. River is acted upon, she is not an actor. The only two exceptions to this in the whole Firefly universe are in the final episode of the series when the entirety of the Firefly crew is incapacitated by the bounty hunter and in the final ten minutes of Serenity when, again, everyone else is busy being dead or dying.

Another great example is the pair of stories You should date an illiterate girl and Date a girl who reads. At a first glance, the second story intends to challenge the treatment of women presented in the first. Yet in both stories the “girls” are seen through male eyes, what is highlighted about their lives is what matters to the male observer and ultimately it is only that male observer’s opinions, views and happiness that seem to count for anything in the worlds created by both writers.

Objectification of women in our culture often goes hand in hand with sexualisation: in addition to being merely objects that are acted upon, women are often presented as sex objects in particular, there entirely for the sexual pleasure and entertainment of male characters and a male audience. Some feminists use “objectification” as shorthand for “sexual objectification”, but I find it useful to keep the two separate, as a character doesn’t have to be sexualised to lack agency.

Agency

Agency is the opposite of objectification. Having agency is being the subject, being the one who acts, who has an effect on the world and others. It’s making choices as a character for one’s own, internally consistent reasons, rather than purely to advance the plot. It is remarkable how few women in our fiction seem to have true agency. Our culture is full of tropes that make female characters little more than plot devices, there only to motivate the male lead in one way or another: the romantic interest, the wife, girlfriend or mother of his children, the sidekick who is there simply to ask stupid questions so she can have the plot explained to her. One of the most jarring examples of the latter is the scene in Casino Royale (the 2006 version) where Vesper Lynd – ostensibly a Treasury accountant, so presumably quite good at maths – has the interminable and dull game of poker explained to her, including basic addition of the amounts of money at stake.

Sometimes, two characters can seem superficially very similar, yet a second look reveals profound differences in the amount of agency they have. Looking at Delirium in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman: Brief Lives, there are some remarkable similarities between her and River Tam in Firefly/Serenity. They both appear as young and vulnerable teenage girls, both have mental health issues and spend large chunks of the story not being very coherent, both actually have considerable powers. Both have moments of clarity where they hold things together while everyone around them falls apart: River in the final episode of the series and the last ten minutes of Firefly; Delirium in Destiny’s garden when Dream works out what he needs to do to find Destruction and has a breakdown as a result.

River’s fight scene at the end of Serenity is fun to watch and it’s pretty epic. It’s also just another way of highlighting how little agency River’s character has. She has spent the entire series and movie being acted upon, being hushed and silenced, being used by others, and her pulling it together enough to save everyone’s ass at the end is just another form of her being used – this time by the writer, as a kind of deus ex machina. River remains an object throughout.

Delirium on the other hand is a fully fleshed-out character, with meaningful relationships with those around her, and heaps of agency. Her siblings may not agree with her, may not want to help her, may even try to use her sometimes, but they listen to her and they talk to her. One of the things Simon pretty much never does with River is ask her a question. Del’s dialog with her siblings in Brief Lives is a constant exchange of questions and answers. They ask her what she wants, why she wants it, how she would achieve it. When Dream mistreats her, she calls him out on it, and he apologises. When she realises that he’s been using her as a distraction and never intended to help her in the first place, again she calls him out on it and after some reflection he apologises and actually resumes their quest. Delirium shapes the events in Brief Lives just as much as Dream does if not more so – it is ultimately her quest that has such a profound impact on him and his relationships with the family.

Despite their superficial similarities, it is the differences between River and Del that highlight quite how much agency one of them lacks and the other has.

Disempowerment

Disempowerment is the process in which a character goes from having agency to becoming an object. It is, unfortunately, the fate of many female characters in our fiction. Simply the act of portraying as tropes, objects and cardboard cut-outs whose lives revolve around the male protagonist disempowers real women. Sometimes, however, the process of disempowerment is made more explicit in the text.

The example that continues to fill me with rage is the fate of Donna Noble in Doctor Who. Donna is taken from her “mundane” existence as a temp, “uplifted” by the Doctor and shown a universe much bigger, scarier, and more wonderful than she could ever have imagined in her previous life. For me personally, Donna was an incredibly powerful character. Due to her age and experience compared to the other modern-era companions I found it much easier to empathise with her. It also felt like she had a more profound impact on the Doctor in many ways, particularly compared to Martha whose defining characteristic was a crush on the Doctor.

As hints began to emerge of a terrible fate lying in wait for Donna, I imagined a gruesome death to save the Doctor, or the Universe, or both. Donna’s actual fate – a mindwipe, completely erasing all memory of her time with the Doctor, and returning her to her everyday life to get married and drudge on in mediocrity ever after – was a low blow indeed. To add insult to injury, the Doctor rocks up incognito to Donna’s wedding and hands over a winning lottery ticket, as if that somehow makes up for stealing a part of her life and personality. She has gone from someone with incredible power – the Doctor’s power – and agency to someone who is acted upon with little free will of her own. Let’s be clear, Donna Noble deserved to die saving the universe and have her name sung in every galaxy until the end of time. That would have been a considerably less disempowering ending than the one she got.

The reason the concepts of agency, objectification and disempowerment matter, the reason the prevalence of the latter two when it comes to female characters in our fiction is problematic should by now be obvious. We tell stories in which women don’t act but are acted upon; or where, if they do act, their agency is immediately taken away and their fate is worse than death. These are the stories we tell little girls about how the world is and how the world should be. Sleeping Beauty is there to be decorative, unconscious, and kissed without her consent; Snow White is there to be poisoned and then revived; Cindarella is to be dressed up – both by her fairy godmother and the prince. Women can be anything but the protagonists of their own stories. Stories matter. They have power. Until women are equal in story, they will continue to struggle to be equal in life.

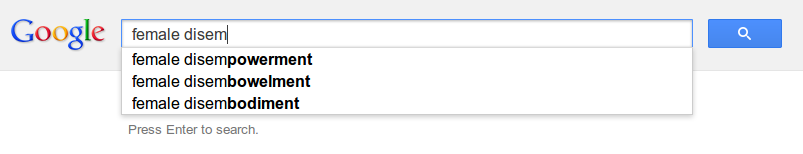

I will leave you with one final, poetic thought from Google:

Part 2

Series Index

Ruining your enjoyment of pop culture – Part 3

Leave a reply