So this month author Mark Forsyth found out that the British Library blocks access to Hamlet on the grounds that it is violent. In pantheons across dimensions, the gods of irony collectively handed in their resignations. Of course, the pertinent question here is not why the institution charged with keeping a “comprehensive collection of books, manuscripts, periodicals, films and other recorded matter, whether printed or otherwise” should censor what is commonly considered one of the greatest works of English literature – I am going to take it as read that that’s frankly ridiculous. Rather, the pertinent question is what on earth is the British Library doing censoring anything in the first place? Therefore, I’d like to examine a few instances where a case might be made for a library of record censoring or restricting access to certain materials.

Read more at ORGZine.

Open Letter to David Cameron on Web Filtering

Dear Prime Minister,

We are writing to you about your proposals for default filtering of the Internet.

You have promised parents ‘one click to protect the whole family’. This is a dangerous and misguided approach. Focusing on a default on filter ignores the importance of sex and relationship education and sexual health. Worse, you are giving parents the impression that if they install Internet filters they can consider their work is done.

We are individuals concerned about the development of healthy sex and relationship attitudes in young people and adults. We believe that the Internet is not simply a danger to children and young people. “Content meant for adults” is not something young people simply need shielding from. Rather, the Internet needs to be an environment in which young people feel safe to develop their opinions and attitudes to sex and gender, especially where they may not feel comfortable talking to authority figures.

So there is also a broader responsibility, faced by the Government and parents, to ensure children and young people are offered consent-based sex and relationship education.

Simply blocking adult material by default will have three negative consequences. First, it will most likely block too much, especially as the filters will cover far more than pornography. It is likely that the filters will unintentionally block important sites related to sexual health, LGBT issues, or sex and relationship education. This will be very damaging for LGBT young people, for example, or vulnerable adults who may be cut off from important support and advice, in particular those with abusive partners who are also the Internet account holder.

Second, it distracts attention away from the need for consent-focused sex and relationship education and support for young people struggling with challenging issues. Third ‘one click to protect the whole family’ offers a false sense of confidence and does nothing to combat the real harms that children face, such as stalking, bullying or grooming.

We were extremely concerned, for example, that the Government voted against compulsory sex and relationship education so recently. This would have done far more to improve young people’s ability to develop healthy relationships than your ineffective Internet filtering proposals.

We would like you to drop your proposals for default on filtering. We urge you instead to invest in a programme of sex and relationship education that empowers young people and to revisit the need for this topic to be mandatory in schools. Please drop shallow headline grabbing proposals and pursue serious and demonstrably effective policies to

tackle abuse of young people.

Yours,

Brooke Magnanti

Laurie Penny

Zoe Margolis

Charles Stross

Jane Fae

Holly Combe

Jane Czyselska

Milena Popova

Also covered in the Independent.

Ruining your enjoyment of pop culture – Part 2

Welcome to Part 2 of my introductory series on feminist critiques of pop culture. In this post, I’ll cover tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle – all lazy writing techniques in which minorities and oppressed groups tend to get the raw end of the deal. I am particularly interested in how these features of our fiction and culture translate into the real world, so I’ll also discuss some of the damage they do in our day-to-day lives.

Tokenisation

Tokenisation is when you throw in a character from a minority or oppressed group in amidst all the cis, het, white, male characters. Woo hoo, aren’t you progressive! One of the many problems with token characters is that they are generally barely even sketched in. From a writing technique point of view you have to rely on tropes and stereotypes to allow the audience to fill in enough blanks to make your story hang together. What that leads to is that we see the same trope or stereotype repeated again and again until we begin to believe that people from that background (women, black people, gay people) are all like that. We get to a point where we only have a single story about a certain “type” of people.

Hogwarts is full for token characters. From Dumbledore, to the Patil twins, to a particularly badly written Cho Chang. Though I must say one of the things I love about the Harry Potter films is that Cho has this amazing Scottish accent. It’s an inspired bit of casting that adds a huge amount of depth to an incredibly flat character. It doesn’t address many of the other issues with Cho, but it does defy the viewer’s expectations and at least make you think. It offers you a different story.

Further Reading

Token Minority on TV Tropes

Some stuff I wrote about token and otherwise stereotypical bisexuals in fiction

Related trope: Black Dude Dies First

Token Gay Guy and his sidekick, Strong Black Chick

To JK Rowling, from Cho Chang

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – The Danger of a Single Story

Othering

Othering is tokenisation’s equally evil twin. Take Pacific Rim for instance. We have an ensemble cast of token characters: the Russian siblings, the Chinese triplets, the “boffins”, the black CO, the meek Japanese woman. These characters’ entire identity is that they are not “wholesome American white boy”. The Russians, despite being just as white as the lead character look profoundly different, and they barely speak. The triplets don’t even have individual names – they are simply the Wei Tang triplets. Mako, despite being raised by Stacker Pentecost from a very young age is a caricature of Western fetishisation of Japanese women, right down to the blue hair streak.

Othering is used as a device to establish distance between a character the audience is meant to identify with and everyone else, thus making the main character more sympathetic. Oh look, this one is like you, root for him. Those others aren’t, don’t worry about them. Othering allows us to forget that these people are just as human as the main character – and as us. It creates a false dichotomy between “them – the others” and “us”. We are in fact so used to thinking that any character we find sympathetic must be just like us, that we are sometimes surprised when they are not, as happened with Rue in Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series.

Othering is often a sign of lazy writing, though it is also sometimes used deliberately to make us feel sympathetic towards a character who is themselves “other” to their audience. In Guy Gavriel Kay’s Under Heaven, a novel set in a fictionalised 8th century China, the main character Shen Tai and his family are shown to have moral values closer to those of a 21st century Western audience, thus othering the rest of Chinese society. Of course the best writers can make you experience the “other” and immerse you in a culture alien to your own to the point when you begin to appreciate the intrinsic humanity. If you are white, read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart to get a sense of how that can be achieved. Manda Scott also does a good job in her Boudica series, as does Cory Doctorow in For the Win.

Othering is a common tool used in politics, and its overuse in fiction makes us all the more receptive to it. When Nick Clegg speaks of Alarm Clock Britain while Cameron and Osborne tell us about skivers, shirkers and scroungers, that’s good cop and bad cop playing a game of othering. When Gillian Duffy talks about flocking Eastern Europeans, that’s othering. When the Home Office live-tweets arrests of “immigration offenders”, that’s othering. And because we’re so conditioned to accept othering in the fictional stories we tell, we swallow it hook, line and sinker in real life too. And the extreme version of othering? That’s when soldiers call the enemy krauts, or towelheads, or terrorists – anything but admitting they are human beings, with lives and families, like you and me.

Further reading

White until proven black: Imagining race in Hunger Games

Othering 101

The Smurfette Principle

The Smurfette Principle is a form of tokenisation. Anita Sarkeesian over at Feminist Frequency does a great job of explaining it, but the short version is that when there is a single female character among an ensemble of male characters you have, for what should be obvious reasons, a Smurfette. Princess Leia? Smurfette. Uhura? Smurfette. Trinity in The Matrix? Smurfette. The interchangeable reporter in The A-Team? Smurfette.

Now whereas for minorities a certain amount tokenisation may perhaps be excused by virtue of them being, well, minorities[1], this is rather more problematic when it comes to representation of women. So if say, roughly one in ten people are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender and you have a cast of five, it’s sometimes okay to have only one LGBT character, or none at all. Women on the other hand make up just over half the human population on earth – women are not a minority. But you wouldn’t know that from the stories we tell.

What is particularly terrifying about the Smurfette Principle is how prevalent it is in real life.

In media…

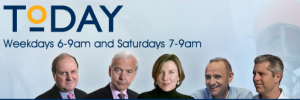

This is the presenter team of the Today Programme, Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show. Today has been on air for 56 years. For 35 of those, there have been female presenters on the programme, but for 18 of those 35 the female presenter has been a Smurfette.

This is the presenter team of the Today Programme, Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show. Today has been on air for 56 years. For 35 of those, there have been female presenters on the programme, but for 18 of those 35 the female presenter has been a Smurfette.

In politics…

You’d think things have got a bit better in the 25 or so years since that photo was taken…

You’d think things have got a bit better in the 25 or so years since that photo was taken…

And they have. There are a total of five women in David Cameron’s cabinet[2]. At this rate, it will take another 50 years to get equal representation in cabinet.

And they have. There are a total of five women in David Cameron’s cabinet[2]. At this rate, it will take another 50 years to get equal representation in cabinet.

In business…

This is the board of directors of Vodafone in 2010. Yep, that’s a Smurfette you see there. Vodafone have acquired another female director since, but I’ll let you do the maths…

This is the board of directors of Vodafone in 2010. Yep, that’s a Smurfette you see there. Vodafone have acquired another female director since, but I’ll let you do the maths…

Remember: Our stories tell us how the world is, but also how the wolrd should be. And right now they’re telling us that Smurfettes are the thing to be! But there’s only so many of us who can be the token woman in an epic fantasy adventure. What do the rest of us do?

Further reading

The Smurfette Principle on the Feminist Frequency

The Smurfette Principle on TV Tropes

In Part 3 I will (probably) talk about agency, objectification and disempowerment.

Part 1

Part 3

Series Index

…in which I ruin your enjoyment of pop culture forever – Part 1

It was pointed out to me that I tweet a lot of feminist critiques of pop culture and that some of my followers would like an introduction or 101 of the concepts I use. Be warned: this series of posts will ruin your enjoyment of popular culture forever. You will go back to your favourite movie or book or TV show and it will never be the same. Proceed at your own peril.

The way this is going to work is that I’ll cover – briefly – some of the key concepts. I will try to give examples (many bad, hopefully some good), and I will try to link you to some further reading. Let’s start by setting the bar as low as it gets, with a couple of numerical methods of analysis: the Bechdel Test, the Austen Exemption and the Sexy Lamp Test.

The Bechdel Test

Coined by Alison Bechdel, the test checks a piece of popular culture (originally movies but works just as well for books and TV shows) for three things:

- Does it have more than one named female character in it?

- Do these female characters at any point in the plot meet and have a conversation?

- Is that conversation about something other than a man?

What is utterly terrifying about this is that the vast majority of our current mainstream cultural output fails this, often at Step 1. Think about the last movie you went to see at the cinema. Mine was Pacific Rim. That has Mako and the Russian mech pilot who did have a name which however escapes me. They never talk to each other. Fail. I actually tracked the Bechdel pass/fail rate in books I read for about a year. Barely half of them passed, and for some of them you really had to squint to see it.

The reason the Bechdel Test is important is that our culture by and large does not tell women’s stories. And stories do two things: they tells us how the world is, but they also tell us how the world should be. They tells us what our society as a whole has decided is good, beautiful, valuable, important and true. Women are romantic interests, tokens, side kicks, objects (we’ll come to all those later). Women are not heroes of their own stories. This is, according to the stories we are telling right now, how the world should be.

Let’s be clear though, passing the Bechdel Test doesn’t get you a feminist gold star. Acknowledging in your work that women exist and are human beings just like men is the bare minimum of human decency. Once you’ve managed that, there’s a whole lot of other issues to contend with, which we will cover in more detail throughout the rest of this series.

Further Reading

A Bechdel Test movie guide

The Bechdel Test on TV Tropes

10 famous films that surprisingly fail the Bechdel Test

The Austen Exemption

This is my very own personal corollary to the Bechdel Test, and it’s that Jane Austen gets a free pass. Why does she need one? Well, her books do have plenty of named female characters who all talk to each other, but on the face of it at least they only ever talk about men.

Except that when Jane and Elizabeth and Charlotte talk about Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy, they talk about £5,000 and £10,000 a year respectively. These are conversations about economics and sociology much more than they are conversations about men. They are conversations about whether you will be able to survive after your parents die and whether the man whom you will be utterly dependent on for said survival will treat you halfway decently. If anything, it is Bingley, Darcy and the like who are utterly objectified in Austen’s novels, and this amuses me somewhat.

No further reading on this one I’m afraid, as I made it up. But feel free to collect your own examples of the Austen Exemption and post them in the comments.

The Sexy Lamp Test

Another test, this was was coined fairly recently by comic writer Kelly Sue DeConnick. It asks a simple question: for any given female character, could you replace her with a sexy lamp without affecting the story? Every Bond girl ever is a sexy lamp. So is Lieutenant Uhura in most of Star Trek (a point beautifully made in Galaxy Quest).

There are subtle differences between the Bechdel Test and the Sexy Lamp Test. It is possible for a work to pass one but not the other. The Harry Potter books, for instance, pass the Bechdel Test easily, but plenty of female characters (Cho Chang comes to mind) are sexy lamps. The converse can also be true: In Run Lola Run, Lola never speaks to another woman through the entire movie, yet she is anything but a sexy lamp.

The Sexy Lamp Test effectively checks for agency (which we’ll come to later, but which essentially means “Does the character do stuff of their own accord?”). Of course the risk here is that we end up with a few token strong women among an army of male characters. The Bechdel Test checks for tokenisation (“Do we only have one female character?”) and encourages more rounded female characters who break out of the “romantic interest” mould, but it can sometimes be passed on a technicality by really rather unremarkable characters.

It’s not that one test is more appropriate or better than the other. Frankly, they are both very basic and crude forms of analysis. The fact that so much of our cultural output still fails one or both of these tests, however, tells me that we might not be ready for anything much more sophisticated.

In Part 2 I will (probably) cover tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle.

Part 2

Series Index

Date whomever you like

This is a response to Date a girl who reads which is itself a response to You should date an illiterate girl.

Date whomever you like

Date whomever you like: a woman who reads, a woman who writes, a woman who does both or neither. But know, above all, this: It is not about you. I, who am all those women, tell my own story.

I am the one with the thousand-page tome in an alphabet you don’t read and a pot of oolong in the teahouse. No, it’s not an awfully big and clever book for a girl like me. I am not a girl, for starters. I am the one next to you on the bus, reading on my phone things that will make you blush and want to reconsider your life. Look over my shoulder at your own peril. I am the one who can barely stutter my way through a menu. I know if I don’t tell my story no other will. I am the one writing insulting notes in the margins of Descartes. It is my book and I can break the spine if I want to. And I am the one with no books but a notebook, scribbling away. If it is about you, you probably don’t want to know.

By all means, ask me if I like my book. But if I glare at you, have the decency to leave. Know that a cup of coffee is not a fair price for my attention – for an hour or even a minute – and that if I choose to talk to you, or sleep with you, it is because I want to, and not in exchange for anything.

Do not assume that if I tell you I understand Ulysses I do it to sound intelligent. For all you know I am the world’s leading scholar on Joyce. I read Austen, Atwood, Le Guin, Parker – as in Dorothy, not Robert or Geoffrey. Look them up. You will be surprised.

If I take you home, I may fuck you – like wildcats in thunderstorms. Or I may make love to you, sweet and gentle, until you fall apart under me. I may have a cunt or a cock, neither of which tells you whether am I a woman or not, and if you don’t like that, the door’s that way. If I stick around, I may choose to be celibate for five years. Again, the door’s that way.

Do not be surprised if I, who can barely read a menu, have a better grasp of language, and of syntax, and of story than you ever will. I know that your language doesn’t have the words for my reality, your syntax cannot circumscribe me, your stories are not mine. Shakespeare never wrote to be read anyway. Do not be surprised when I learn to read.

Do not propose. Or if you do, do not expect me to say yes, or wear white, or want to have your children. I may do all of these things, or none. I will not make you the meaning of my life, and I will thank you to not make me the meaning of yours.

You can tell your own story. You can come along for the ride. But this story? It is mine.

ETA 04/09/13: I recorded a reading of this. You can listen to it:

[Elsewhere] Truthloader: Is David Cameron’s porn filter a good idea?

I was on Truthloader’s live debate yesterday talking about web filtering and some of the other things this government should be doing instead:

Ruining your enjoyment of pop culture – Start Here

This is written in December 2013 and backdated deliberately.

I am writing a slightly meandering and still ongoing series of posts on feminist critiques of pop culture. It’s intended as introductory reading, to give people tools to examine our cultural output and think about it critically. This post serves as as the entryway to that series.

Part 1: in which we discuss the Bechdel Test, the Austen Exemption and the Sexy Lamp Test. Spoiler warnings for: Pacific Rim, Pride and Prejudice, Run Lola Run.

Part 2: in which we discuss tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle. Spoiler warnings for: Harry Potter, Pacific Rim, the Hunger Games trilogy, Guy Gavriel Kay’s Under Heaven.

Part 3: in which we discuss women as objects, agency, and disempowerment. Spoiler warnings for: Sandman (Brief Lives in particular), Firefly/Serenity, Doctor Who (the Donna season), Casino Royale.

An honourary mention goes to a short piece of fiction I wrote, Date Whomever You Like.

Censored

Imagine that last week you’d read a blog post. It was post about porn blocking, and how there are other things we as a society should focus on if, say, we wanted to prevent child sexual abuse. It was a post about porn blocking from an abuse survivor.

One of the many people you follow on Twitter or are friends with on Facebook posted the link, and you followed it. You read the post, maybe you thought the author had made a good point or two, then you closed the tab, and that was that. Then a couple of days later you found yourself discussing porn blocking with a colleague, or a friend, and you thought, “Damn, I should link them to that post. Wonder how I find it again.”

It was a post about porn blocking from an abuse survivor. What search terms might you give Google to help you find it? The top ten search terms to hit my blog this month are (and they’re not pretty):

- abuse porn

- porn abuse

- milena popova

- survivor porn

- abused porn

- market failure examples 2011[1]

- bi threesomes[2]

- child sex porn

- abuse porn.

- milena porn

Now, something you might have missed what with the royal baby hype is that David Cameron’s speech actually proposed three completely unrelated measures, and that everyone has been conflating them ever since. They are

- default-on filters at ISP level targeting pornography “and also perhaps self-harming sites”, where you would actively have to notify your ISP if you wanted the filter disabled;

- getting the major search engines not to return any results for search terms associated with child sexual abuse;

- and banning possession of pornography depicting simulated rape.

That’s right. Under that second proposal, nearly a quarter of people who googled for a specific post on my blog this month would have had no search results returned to them. Is there a chance that one or two of these people were actually searching for child abuse images? Yeah, perhaps. Were the vast majority of them genuinely looking for my blog post, using the search terms most likely to find it? Yep.

David Cameron’s proposals would silence me when I speak out about child abuse and porn blocking. They would silence many others, too. Next time someone tells you they spoke to the man from Google [~21mins in] and it’ll all be fine really, do remind them that they are conflating three separate measures, all of which are highly likely to be ineffective in actually protecting children, and some of which are indeed equivalent to censorship.

Oh and do sign the Open Rights Group petition against porn blocking.

—

[1] A variation on this seems to make the Top 10 every month. I’m guessing this post has somehow made it onto a first-year economics reading list.

[2] Remember, just because someone is bisexual doesn’t mean they want a threesome with you.

[TW: child sexual abuse] Porn blocking – a survivor’s perspective

I am a survivor: when I was a teenager, I was sexually abused by an uncle. So when David Cameron proposes a raft of measures which amount to censorship of the internet, all in the name of protecting “our children and their innocence”, I find that deeply offensive.

I am not going to tell you about the potential harmful side effects of these measures, or why none of them are actually going to work. Other people can do this far better than me.

Instead, I want to move on this debate. I want to tell you about some of the factors in my environment that made my abuse possible, because maybe that will give Mr Cameron some idea of the real issues he needs to tackle if he wants to protect children [1].

Like many kids today, I grew up in an environment where parents were deeply uncomfortable talking about bodies, or sex and sexuality. When I got my first period, my mother gave me the most boring textbook in the universe to read. It covered basic anatomy and mechanics of sex, but I must admit I didn’t get very far into it. A year or so later she arranged for me to have a chat with her gynaecologist, who was a friend of the family. What I would have learned from that chat, had I not had access to other materials on sex and relationships, was that oral sex is dirty and horrible and not something one should ever engage in. What I actually learned from the whole experience was that my parents were not willing to discuss issues of sex and sexuality with me. So when the abuse happened, when I would have needed to discuss those things with them and get help, I didn’t feel able to do so.

Now, I appreciate the argument that simply saying “leave child protection exclusively to parents” is middle class privilege. However many parents, middle class and otherwise, would greatly benefit from some help and advice on how to approach difficult issues like sex, sexuality and relationships with their children, and how to create a safe space where children can raise concerns and ask questions without fear of being judged or getting into trouble.

Like many girls today, I also grew up in an environment where a woman’s sense of self-worth was directly proportional to how liked she was by others, particularly men. That translated into being conditioned to be less confrontational, always having to be polite, being told I needed to keep the peace regardless of personal cost. This is not a great way to learn to establish and enforce personal boundaries. When the man who harassed me on the way to school told me it wasn’t very nice to tell him to fuck off, I felt guilty.

Here’s the thing: You know what the most insidious part of our culture is that sends precisely those hugely damaging messages to girls and women? No, it’s not porn. It’s romantic comedies. The idea that behaviour which amounts to stalking and sexual assault is romantic is deeply ingrained in the genre; and trust me – many more kids have access to romantic comedies from a much earlier age than they do to porn. If you want to talk about normalising the idea of violence against women, it’s there that I’d start, not at rape porn. Of course this doesn’t mean I want to ban romantic comedies. However, helping both parents at teachers look critically at the damaging parts of our mainstream culture and discuss them with children would protect many more children than filtering pornography.

Like many kids today, I received sex education that was patchy, focused on the mechanics and on avoiding pregnancy and STIs. Oh, and some of it was distinctly anti-abortion – talk about personal boundaries and bodily autonomy elsewhere. At no point was pleasure discussed. At no point did we ever talk about consent. At not point did a teacher make me feel like I could ask questions, express concerns or confide in them. I knew all about the mechanics of sex. I had a very good idea of what was happening to me when I was being abused. I had no idea how to stop it.

This is the biggest bone I have to pick with the government on this subject. David Cameron has the audacity to tell us that the solution to children viewing pornography is both “about access and (…) about education”. Yet the kind of education he means is not sex and relationships education – it’s education about “online safety”. At the same time his Education Secretary can’t even utter the words “sex and relationship education” without sniggering like a 12-year-old behind the bike sheds. His party (and the LibDems) almost unanimously voted against an amendment to the Children and Families Bill which would have created a statutory provision for sex and relationship education in the national curriculum.

Pornography (extreme or otherwise) and images of child sexual abuse (vile though they are) played absolutely no role in my abuse. I am not going to argue that they play no role at all in anyone’s abuse, or that without the proper context they can’t be damaging to children and young people. What David Cameron is doing, however, is lulling us all into a false sense of security while actively working against measures which would genuinely protect children and young people. This is not a man who is well-intentioned and ill-advised. This is a man who is deeply cynical and hypocritical; a man – and a government – incapable of doing the right thing, and only capable of doing the easy, wrong thing which will gain them votes. This is a man who should hang his head in shame.

As an abuse survivor, I find the measures outlined by the Prime Minister today objectionable, offensive and disgusting. As an abuse survivor, I demand that this government face the facts and either admit that they have no intention whatsoever of protecting children or actually put measures on the table which will do so. As an abuse survivor, I hold my head high today – but I don’t think David Cameron should.

—

[1] While I do believe children need protection from some things, I find the talk of protecting their “innocence” deeply squicky and disturbing. Kids do not become guilty once they find out about sex.

Let me vote: a public service announcement

Those of you who’ve been reading this blog since 2010 will probably know this, but it struck me this week that many of you don’t. So here is a public service announcement on the intersection between democracy and being an immigrant.

I appreciate that my origin and citizenship status are somewhat murky, not helped by the fact that I self-identify as European. I was born in Bulgaria, I left there when I was 10 and at the age of 16 I was granted Austrian citizenship. I have lived in the UK for 14 years now, longer than in any other country. I am still legally Austrian, and only Austrian. Austria is somewhat particular about dual nationality (basically, if you’re Arnold Schwarzenegger, governor of California, you’re allowed it; if you’re me the hoops are not worth jumping through). I would technically qualify for UK citizenship but I have good reasons – none of them sentimental – to hang on to my Austrian passport.

I am registered to vote in the UK, but as an EU citizen, I can only do so in local and European Parliament elections – not general elections. I can vote in general elections in Austria but I never have. By the time the first elections after my 18th birthday [1] came around I had left the country and was reasonably sure I wasn’t going back.

Here’s what I am allowed to do in the UK: I’m allowed to pay tax. Quite a lot of it. [2] I am, in all fairness, allowed to be mouthy and obnoxious about being an immigrant, sometimes even in the national press. I am allowed to ruin a good pair of shoes in aid of a national referendum campaign. But I’m not allowed to vote in said referendum. I am allowed to be blamed for every single failure of this government. But I don’t have a say in who forms the next one.

This is where Let Me Vote comes in. Let Me Vote is a European Citizens’ Initiative – if it manages to collect 1,000,000 signatures from EU citizens, the European Commission will at least have to think about putting forward legislation to allow EU citizens resident in other EU countries to vote in their country of residence. It would remove one more of the millions of barriers to the free movement of people within the Union. It would mean that we would no longer be second-class people the minute we set foot outside our country of citizenship – at least politically. It would mean that when your Mum and Dad retire to Spain or Bulgaria, they would have a political say in what happens around them.

If you’re worried about immigrants voting in your country, remember that Commonwealth citizens are already allowed to vote in general elections in the UK. Also remember that lots of British people move abroad, and after 15 years they lose the right to vote in the UK, leaving them in a strange kind of political purgatory where there is nowhere for them to exercise their democratic rights. Remember that even if you reduce the European Union to its economic basics, the Common Market is still about the free movement of goods, services, capital and people.

So head over to Let Me Vote and sign the ECI.

—

[1] Austria lowered the voting age to 16 in 2007.

[2] Note that I don’t think my tax payer status entitles me to anything. But with the amount of immigrant scapegoating in British political rhetoric, it’s become a reflex to point it out.