Welcome back to my meandering series on feminist critques of pop culture. In Part 1 we looked at some very crude tests to see if a work of fiction contained any even vaguely realistic female characters at all and were perhaps surprised by how much of our current cultural output fails these basic tests.

In Part 2, we looked at some common, and generally sloppy, writing techniques which serve to marginalise female and minority characters in fiction.

Today, I want to talk about how women are allowed to act in fiction. I’ll cover three concepts that are deeply interconnected: Objectification, agency and disempowerment.

Spoilers ahead for: Sandman (Brief Lives in particular), Firefly/Serenity, Doctor Who (the Donna season), Casino Royale.

Women as objects

In grammar, the subject of a sentence is the one who acts, the object the one being acted upon. So in the sentence “Jill threw the ball”, Jill is the subject, and the ball is the object. The objectification of women is one of the most prevalent phenomena in our popular culture today. If you think back to the Sexy Lamp Test for a moment, you’ll realise that objectification is precisely what it tests for. In many works of fiction, even the few female characters that are around often don’t act of their own free will but are acted upon instead.

Let’s take River Tam in Firefly as an example. The first time we meet River, she is quite literally delivered in a box. To make matters worse, she spends most of the first episode being naked and afraid, presumably for someone’s viewing pleasure. Throughout the series and in Serenity, River is repeatedly silenced, wheeled around in boxes and chairs, and generally prevented from doing anything of her own accord. At the start of Serenity, we see Simon and Mal arguing over whether River should join the crew on a bank robbery. River’s own will is never taken into account in this. River is acted upon, she is not an actor. The only two exceptions to this in the whole Firefly universe are in the final episode of the series when the entirety of the Firefly crew is incapacitated by the bounty hunter and in the final ten minutes of Serenity when, again, everyone else is busy being dead or dying.

Another great example is the pair of stories You should date an illiterate girl and Date a girl who reads. At a first glance, the second story intends to challenge the treatment of women presented in the first. Yet in both stories the “girls” are seen through male eyes, what is highlighted about their lives is what matters to the male observer and ultimately it is only that male observer’s opinions, views and happiness that seem to count for anything in the worlds created by both writers.

Objectification of women in our culture often goes hand in hand with sexualisation: in addition to being merely objects that are acted upon, women are often presented as sex objects in particular, there entirely for the sexual pleasure and entertainment of male characters and a male audience. Some feminists use “objectification” as shorthand for “sexual objectification”, but I find it useful to keep the two separate, as a character doesn’t have to be sexualised to lack agency.

Agency

Agency is the opposite of objectification. Having agency is being the subject, being the one who acts, who has an effect on the world and others. It’s making choices as a character for one’s own, internally consistent reasons, rather than purely to advance the plot. It is remarkable how few women in our fiction seem to have true agency. Our culture is full of tropes that make female characters little more than plot devices, there only to motivate the male lead in one way or another: the romantic interest, the wife, girlfriend or mother of his children, the sidekick who is there simply to ask stupid questions so she can have the plot explained to her. One of the most jarring examples of the latter is the scene in Casino Royale (the 2006 version) where Vesper Lynd – ostensibly a Treasury accountant, so presumably quite good at maths – has the interminable and dull game of poker explained to her, including basic addition of the amounts of money at stake.

Sometimes, two characters can seem superficially very similar, yet a second look reveals profound differences in the amount of agency they have. Looking at Delirium in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman: Brief Lives, there are some remarkable similarities between her and River Tam in Firefly/Serenity. They both appear as young and vulnerable teenage girls, both have mental health issues and spend large chunks of the story not being very coherent, both actually have considerable powers. Both have moments of clarity where they hold things together while everyone around them falls apart: River in the final episode of the series and the last ten minutes of Firefly; Delirium in Destiny’s garden when Dream works out what he needs to do to find Destruction and has a breakdown as a result.

River’s fight scene at the end of Serenity is fun to watch and it’s pretty epic. It’s also just another way of highlighting how little agency River’s character has. She has spent the entire series and movie being acted upon, being hushed and silenced, being used by others, and her pulling it together enough to save everyone’s ass at the end is just another form of her being used – this time by the writer, as a kind of deus ex machina. River remains an object throughout.

Delirium on the other hand is a fully fleshed-out character, with meaningful relationships with those around her, and heaps of agency. Her siblings may not agree with her, may not want to help her, may even try to use her sometimes, but they listen to her and they talk to her. One of the things Simon pretty much never does with River is ask her a question. Del’s dialog with her siblings in Brief Lives is a constant exchange of questions and answers. They ask her what she wants, why she wants it, how she would achieve it. When Dream mistreats her, she calls him out on it, and he apologises. When she realises that he’s been using her as a distraction and never intended to help her in the first place, again she calls him out on it and after some reflection he apologises and actually resumes their quest. Delirium shapes the events in Brief Lives just as much as Dream does if not more so – it is ultimately her quest that has such a profound impact on him and his relationships with the family.

Despite their superficial similarities, it is the differences between River and Del that highlight quite how much agency one of them lacks and the other has.

Disempowerment

Disempowerment is the process in which a character goes from having agency to becoming an object. It is, unfortunately, the fate of many female characters in our fiction. Simply the act of portraying as tropes, objects and cardboard cut-outs whose lives revolve around the male protagonist disempowers real women. Sometimes, however, the process of disempowerment is made more explicit in the text.

The example that continues to fill me with rage is the fate of Donna Noble in Doctor Who. Donna is taken from her “mundane” existence as a temp, “uplifted” by the Doctor and shown a universe much bigger, scarier, and more wonderful than she could ever have imagined in her previous life. For me personally, Donna was an incredibly powerful character. Due to her age and experience compared to the other modern-era companions I found it much easier to empathise with her. It also felt like she had a more profound impact on the Doctor in many ways, particularly compared to Martha whose defining characteristic was a crush on the Doctor.

As hints began to emerge of a terrible fate lying in wait for Donna, I imagined a gruesome death to save the Doctor, or the Universe, or both. Donna’s actual fate – a mindwipe, completely erasing all memory of her time with the Doctor, and returning her to her everyday life to get married and drudge on in mediocrity ever after – was a low blow indeed. To add insult to injury, the Doctor rocks up incognito to Donna’s wedding and hands over a winning lottery ticket, as if that somehow makes up for stealing a part of her life and personality. She has gone from someone with incredible power – the Doctor’s power – and agency to someone who is acted upon with little free will of her own. Let’s be clear, Donna Noble deserved to die saving the universe and have her name sung in every galaxy until the end of time. That would have been a considerably less disempowering ending than the one she got.

The reason the concepts of agency, objectification and disempowerment matter, the reason the prevalence of the latter two when it comes to female characters in our fiction is problematic should by now be obvious. We tell stories in which women don’t act but are acted upon; or where, if they do act, their agency is immediately taken away and their fate is worse than death. These are the stories we tell little girls about how the world is and how the world should be. Sleeping Beauty is there to be decorative, unconscious, and kissed without her consent; Snow White is there to be poisoned and then revived; Cindarella is to be dressed up – both by her fairy godmother and the prince. Women can be anything but the protagonists of their own stories. Stories matter. They have power. Until women are equal in story, they will continue to struggle to be equal in life.

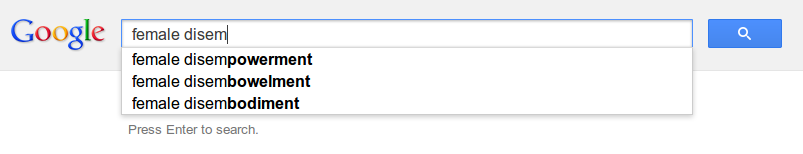

I will leave you with one final, poetic thought from Google:

Part 2

Series Index

Monthly Archives: August 2013

[Elsewhere] Hamlet and the British Library

So this month author Mark Forsyth found out that the British Library blocks access to Hamlet on the grounds that it is violent. In pantheons across dimensions, the gods of irony collectively handed in their resignations. Of course, the pertinent question here is not why the institution charged with keeping a “comprehensive collection of books, manuscripts, periodicals, films and other recorded matter, whether printed or otherwise” should censor what is commonly considered one of the greatest works of English literature – I am going to take it as read that that’s frankly ridiculous. Rather, the pertinent question is what on earth is the British Library doing censoring anything in the first place? Therefore, I’d like to examine a few instances where a case might be made for a library of record censoring or restricting access to certain materials.

Read more at ORGZine.

Open Letter to David Cameron on Web Filtering

Dear Prime Minister,

We are writing to you about your proposals for default filtering of the Internet.

You have promised parents ‘one click to protect the whole family’. This is a dangerous and misguided approach. Focusing on a default on filter ignores the importance of sex and relationship education and sexual health. Worse, you are giving parents the impression that if they install Internet filters they can consider their work is done.

We are individuals concerned about the development of healthy sex and relationship attitudes in young people and adults. We believe that the Internet is not simply a danger to children and young people. “Content meant for adults” is not something young people simply need shielding from. Rather, the Internet needs to be an environment in which young people feel safe to develop their opinions and attitudes to sex and gender, especially where they may not feel comfortable talking to authority figures.

So there is also a broader responsibility, faced by the Government and parents, to ensure children and young people are offered consent-based sex and relationship education.

Simply blocking adult material by default will have three negative consequences. First, it will most likely block too much, especially as the filters will cover far more than pornography. It is likely that the filters will unintentionally block important sites related to sexual health, LGBT issues, or sex and relationship education. This will be very damaging for LGBT young people, for example, or vulnerable adults who may be cut off from important support and advice, in particular those with abusive partners who are also the Internet account holder.

Second, it distracts attention away from the need for consent-focused sex and relationship education and support for young people struggling with challenging issues. Third ‘one click to protect the whole family’ offers a false sense of confidence and does nothing to combat the real harms that children face, such as stalking, bullying or grooming.

We were extremely concerned, for example, that the Government voted against compulsory sex and relationship education so recently. This would have done far more to improve young people’s ability to develop healthy relationships than your ineffective Internet filtering proposals.

We would like you to drop your proposals for default on filtering. We urge you instead to invest in a programme of sex and relationship education that empowers young people and to revisit the need for this topic to be mandatory in schools. Please drop shallow headline grabbing proposals and pursue serious and demonstrably effective policies to

tackle abuse of young people.

Yours,

Brooke Magnanti

Laurie Penny

Zoe Margolis

Charles Stross

Jane Fae

Holly Combe

Jane Czyselska

Milena Popova

Also covered in the Independent.

Ruining your enjoyment of pop culture – Part 2

Welcome to Part 2 of my introductory series on feminist critiques of pop culture. In this post, I’ll cover tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle – all lazy writing techniques in which minorities and oppressed groups tend to get the raw end of the deal. I am particularly interested in how these features of our fiction and culture translate into the real world, so I’ll also discuss some of the damage they do in our day-to-day lives.

Tokenisation

Tokenisation is when you throw in a character from a minority or oppressed group in amidst all the cis, het, white, male characters. Woo hoo, aren’t you progressive! One of the many problems with token characters is that they are generally barely even sketched in. From a writing technique point of view you have to rely on tropes and stereotypes to allow the audience to fill in enough blanks to make your story hang together. What that leads to is that we see the same trope or stereotype repeated again and again until we begin to believe that people from that background (women, black people, gay people) are all like that. We get to a point where we only have a single story about a certain “type” of people.

Hogwarts is full for token characters. From Dumbledore, to the Patil twins, to a particularly badly written Cho Chang. Though I must say one of the things I love about the Harry Potter films is that Cho has this amazing Scottish accent. It’s an inspired bit of casting that adds a huge amount of depth to an incredibly flat character. It doesn’t address many of the other issues with Cho, but it does defy the viewer’s expectations and at least make you think. It offers you a different story.

Further Reading

Token Minority on TV Tropes

Some stuff I wrote about token and otherwise stereotypical bisexuals in fiction

Related trope: Black Dude Dies First

Token Gay Guy and his sidekick, Strong Black Chick

To JK Rowling, from Cho Chang

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – The Danger of a Single Story

Othering

Othering is tokenisation’s equally evil twin. Take Pacific Rim for instance. We have an ensemble cast of token characters: the Russian siblings, the Chinese triplets, the “boffins”, the black CO, the meek Japanese woman. These characters’ entire identity is that they are not “wholesome American white boy”. The Russians, despite being just as white as the lead character look profoundly different, and they barely speak. The triplets don’t even have individual names – they are simply the Wei Tang triplets. Mako, despite being raised by Stacker Pentecost from a very young age is a caricature of Western fetishisation of Japanese women, right down to the blue hair streak.

Othering is used as a device to establish distance between a character the audience is meant to identify with and everyone else, thus making the main character more sympathetic. Oh look, this one is like you, root for him. Those others aren’t, don’t worry about them. Othering allows us to forget that these people are just as human as the main character – and as us. It creates a false dichotomy between “them – the others” and “us”. We are in fact so used to thinking that any character we find sympathetic must be just like us, that we are sometimes surprised when they are not, as happened with Rue in Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series.

Othering is often a sign of lazy writing, though it is also sometimes used deliberately to make us feel sympathetic towards a character who is themselves “other” to their audience. In Guy Gavriel Kay’s Under Heaven, a novel set in a fictionalised 8th century China, the main character Shen Tai and his family are shown to have moral values closer to those of a 21st century Western audience, thus othering the rest of Chinese society. Of course the best writers can make you experience the “other” and immerse you in a culture alien to your own to the point when you begin to appreciate the intrinsic humanity. If you are white, read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart to get a sense of how that can be achieved. Manda Scott also does a good job in her Boudica series, as does Cory Doctorow in For the Win.

Othering is a common tool used in politics, and its overuse in fiction makes us all the more receptive to it. When Nick Clegg speaks of Alarm Clock Britain while Cameron and Osborne tell us about skivers, shirkers and scroungers, that’s good cop and bad cop playing a game of othering. When Gillian Duffy talks about flocking Eastern Europeans, that’s othering. When the Home Office live-tweets arrests of “immigration offenders”, that’s othering. And because we’re so conditioned to accept othering in the fictional stories we tell, we swallow it hook, line and sinker in real life too. And the extreme version of othering? That’s when soldiers call the enemy krauts, or towelheads, or terrorists – anything but admitting they are human beings, with lives and families, like you and me.

Further reading

White until proven black: Imagining race in Hunger Games

Othering 101

The Smurfette Principle

The Smurfette Principle is a form of tokenisation. Anita Sarkeesian over at Feminist Frequency does a great job of explaining it, but the short version is that when there is a single female character among an ensemble of male characters you have, for what should be obvious reasons, a Smurfette. Princess Leia? Smurfette. Uhura? Smurfette. Trinity in The Matrix? Smurfette. The interchangeable reporter in The A-Team? Smurfette.

Now whereas for minorities a certain amount tokenisation may perhaps be excused by virtue of them being, well, minorities[1], this is rather more problematic when it comes to representation of women. So if say, roughly one in ten people are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender and you have a cast of five, it’s sometimes okay to have only one LGBT character, or none at all. Women on the other hand make up just over half the human population on earth – women are not a minority. But you wouldn’t know that from the stories we tell.

What is particularly terrifying about the Smurfette Principle is how prevalent it is in real life.

In media…

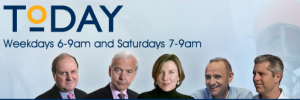

This is the presenter team of the Today Programme, Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show. Today has been on air for 56 years. For 35 of those, there have been female presenters on the programme, but for 18 of those 35 the female presenter has been a Smurfette.

This is the presenter team of the Today Programme, Radio 4’s flagship news and current affairs show. Today has been on air for 56 years. For 35 of those, there have been female presenters on the programme, but for 18 of those 35 the female presenter has been a Smurfette.

In politics…

You’d think things have got a bit better in the 25 or so years since that photo was taken…

You’d think things have got a bit better in the 25 or so years since that photo was taken…

And they have. There are a total of five women in David Cameron’s cabinet[2]. At this rate, it will take another 50 years to get equal representation in cabinet.

And they have. There are a total of five women in David Cameron’s cabinet[2]. At this rate, it will take another 50 years to get equal representation in cabinet.

In business…

This is the board of directors of Vodafone in 2010. Yep, that’s a Smurfette you see there. Vodafone have acquired another female director since, but I’ll let you do the maths…

This is the board of directors of Vodafone in 2010. Yep, that’s a Smurfette you see there. Vodafone have acquired another female director since, but I’ll let you do the maths…

Remember: Our stories tell us how the world is, but also how the wolrd should be. And right now they’re telling us that Smurfettes are the thing to be! But there’s only so many of us who can be the token woman in an epic fantasy adventure. What do the rest of us do?

Further reading

The Smurfette Principle on the Feminist Frequency

The Smurfette Principle on TV Tropes

In Part 3 I will (probably) talk about agency, objectification and disempowerment.

Part 1

Part 3

Series Index

…in which I ruin your enjoyment of pop culture forever – Part 1

It was pointed out to me that I tweet a lot of feminist critiques of pop culture and that some of my followers would like an introduction or 101 of the concepts I use. Be warned: this series of posts will ruin your enjoyment of popular culture forever. You will go back to your favourite movie or book or TV show and it will never be the same. Proceed at your own peril.

The way this is going to work is that I’ll cover – briefly – some of the key concepts. I will try to give examples (many bad, hopefully some good), and I will try to link you to some further reading. Let’s start by setting the bar as low as it gets, with a couple of numerical methods of analysis: the Bechdel Test, the Austen Exemption and the Sexy Lamp Test.

The Bechdel Test

Coined by Alison Bechdel, the test checks a piece of popular culture (originally movies but works just as well for books and TV shows) for three things:

- Does it have more than one named female character in it?

- Do these female characters at any point in the plot meet and have a conversation?

- Is that conversation about something other than a man?

What is utterly terrifying about this is that the vast majority of our current mainstream cultural output fails this, often at Step 1. Think about the last movie you went to see at the cinema. Mine was Pacific Rim. That has Mako and the Russian mech pilot who did have a name which however escapes me. They never talk to each other. Fail. I actually tracked the Bechdel pass/fail rate in books I read for about a year. Barely half of them passed, and for some of them you really had to squint to see it.

The reason the Bechdel Test is important is that our culture by and large does not tell women’s stories. And stories do two things: they tells us how the world is, but they also tell us how the world should be. They tells us what our society as a whole has decided is good, beautiful, valuable, important and true. Women are romantic interests, tokens, side kicks, objects (we’ll come to all those later). Women are not heroes of their own stories. This is, according to the stories we are telling right now, how the world should be.

Let’s be clear though, passing the Bechdel Test doesn’t get you a feminist gold star. Acknowledging in your work that women exist and are human beings just like men is the bare minimum of human decency. Once you’ve managed that, there’s a whole lot of other issues to contend with, which we will cover in more detail throughout the rest of this series.

Further Reading

A Bechdel Test movie guide

The Bechdel Test on TV Tropes

10 famous films that surprisingly fail the Bechdel Test

The Austen Exemption

This is my very own personal corollary to the Bechdel Test, and it’s that Jane Austen gets a free pass. Why does she need one? Well, her books do have plenty of named female characters who all talk to each other, but on the face of it at least they only ever talk about men.

Except that when Jane and Elizabeth and Charlotte talk about Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy, they talk about £5,000 and £10,000 a year respectively. These are conversations about economics and sociology much more than they are conversations about men. They are conversations about whether you will be able to survive after your parents die and whether the man whom you will be utterly dependent on for said survival will treat you halfway decently. If anything, it is Bingley, Darcy and the like who are utterly objectified in Austen’s novels, and this amuses me somewhat.

No further reading on this one I’m afraid, as I made it up. But feel free to collect your own examples of the Austen Exemption and post them in the comments.

The Sexy Lamp Test

Another test, this was was coined fairly recently by comic writer Kelly Sue DeConnick. It asks a simple question: for any given female character, could you replace her with a sexy lamp without affecting the story? Every Bond girl ever is a sexy lamp. So is Lieutenant Uhura in most of Star Trek (a point beautifully made in Galaxy Quest).

There are subtle differences between the Bechdel Test and the Sexy Lamp Test. It is possible for a work to pass one but not the other. The Harry Potter books, for instance, pass the Bechdel Test easily, but plenty of female characters (Cho Chang comes to mind) are sexy lamps. The converse can also be true: In Run Lola Run, Lola never speaks to another woman through the entire movie, yet she is anything but a sexy lamp.

The Sexy Lamp Test effectively checks for agency (which we’ll come to later, but which essentially means “Does the character do stuff of their own accord?”). Of course the risk here is that we end up with a few token strong women among an army of male characters. The Bechdel Test checks for tokenisation (“Do we only have one female character?”) and encourages more rounded female characters who break out of the “romantic interest” mould, but it can sometimes be passed on a technicality by really rather unremarkable characters.

It’s not that one test is more appropriate or better than the other. Frankly, they are both very basic and crude forms of analysis. The fact that so much of our cultural output still fails one or both of these tests, however, tells me that we might not be ready for anything much more sophisticated.

In Part 2 I will (probably) cover tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle.

Part 2

Series Index

Date whomever you like

This is a response to Date a girl who reads which is itself a response to You should date an illiterate girl.

Date whomever you like

Date whomever you like: a woman who reads, a woman who writes, a woman who does both or neither. But know, above all, this: It is not about you. I, who am all those women, tell my own story.

I am the one with the thousand-page tome in an alphabet you don’t read and a pot of oolong in the teahouse. No, it’s not an awfully big and clever book for a girl like me. I am not a girl, for starters. I am the one next to you on the bus, reading on my phone things that will make you blush and want to reconsider your life. Look over my shoulder at your own peril. I am the one who can barely stutter my way through a menu. I know if I don’t tell my story no other will. I am the one writing insulting notes in the margins of Descartes. It is my book and I can break the spine if I want to. And I am the one with no books but a notebook, scribbling away. If it is about you, you probably don’t want to know.

By all means, ask me if I like my book. But if I glare at you, have the decency to leave. Know that a cup of coffee is not a fair price for my attention – for an hour or even a minute – and that if I choose to talk to you, or sleep with you, it is because I want to, and not in exchange for anything.

Do not assume that if I tell you I understand Ulysses I do it to sound intelligent. For all you know I am the world’s leading scholar on Joyce. I read Austen, Atwood, Le Guin, Parker – as in Dorothy, not Robert or Geoffrey. Look them up. You will be surprised.

If I take you home, I may fuck you – like wildcats in thunderstorms. Or I may make love to you, sweet and gentle, until you fall apart under me. I may have a cunt or a cock, neither of which tells you whether am I a woman or not, and if you don’t like that, the door’s that way. If I stick around, I may choose to be celibate for five years. Again, the door’s that way.

Do not be surprised if I, who can barely read a menu, have a better grasp of language, and of syntax, and of story than you ever will. I know that your language doesn’t have the words for my reality, your syntax cannot circumscribe me, your stories are not mine. Shakespeare never wrote to be read anyway. Do not be surprised when I learn to read.

Do not propose. Or if you do, do not expect me to say yes, or wear white, or want to have your children. I may do all of these things, or none. I will not make you the meaning of my life, and I will thank you to not make me the meaning of yours.

You can tell your own story. You can come along for the ride. But this story? It is mine.

ETA 04/09/13: I recorded a reading of this. You can listen to it:

[Elsewhere] Truthloader: Is David Cameron’s porn filter a good idea?

I was on Truthloader’s live debate yesterday talking about web filtering and some of the other things this government should be doing instead:

Ruining your enjoyment of pop culture – Start Here

This is written in December 2013 and backdated deliberately.

I am writing a slightly meandering and still ongoing series of posts on feminist critiques of pop culture. It’s intended as introductory reading, to give people tools to examine our cultural output and think about it critically. This post serves as as the entryway to that series.

Part 1: in which we discuss the Bechdel Test, the Austen Exemption and the Sexy Lamp Test. Spoiler warnings for: Pacific Rim, Pride and Prejudice, Run Lola Run.

Part 2: in which we discuss tokenisation, othering and the Smurfette Principle. Spoiler warnings for: Harry Potter, Pacific Rim, the Hunger Games trilogy, Guy Gavriel Kay’s Under Heaven.

Part 3: in which we discuss women as objects, agency, and disempowerment. Spoiler warnings for: Sandman (Brief Lives in particular), Firefly/Serenity, Doctor Who (the Donna season), Casino Royale.

An honourary mention goes to a short piece of fiction I wrote, Date Whomever You Like.