I’m struggling to even begin to enumerate the ways in which the Church of England’s decision on gay bishops is deeply wrong.

Let’s start with the obvious: apparently if you are a gay man in a civil partnership, you may now become a bishop in this country’s established church as long as you a. promise to be celibate and b. repent your evil ways “homosexual activity” of the past. So while your straight colleagues may continue to enjoy the physical as well as emotional benefits of their marriages, the Church will presumably install a webcam in your bedroom, or make you and your partner sleep in separate beds. This of course will do your relationship a world of good, thus enabling you to excel at your job and minister to your congregation ever so much better. Not.

This arrangement is hardly compatible with the duty of care normally owed by an employer to an employee. The Church, however, has a neat way around that, in that clergy are not legally regarded as employees. They have no contract of employment but are technically office holders – a clever trick which allows the Church to get around a whole bunch of employment legislation.

Funnily enough, both the opponent and proponent of the move to allow gay bishops that Radio 4’s PM managed to get on air today thought that the proposed set-up was ridiculous, unenforceable and damaging to the Church’s credibility. But that’s hardly anything new for the CofE. Also unsurprisingly, they then went on to reach very different conclusions from this shared opinion.

The decision, combined with the pre-Christmas fiasco over women bishops, also highlights another longstanding issue: that it is still easier to reach the top tiers of society as a gay man than as a woman of any sexual orientation. In privilege bingo gender apparently trumps sexual orientation every time. The Church has been debating the ordination of female clergy since 1966, and of women bishops in particular since 1975, and an end to this debate does not appear to be in sight. Ridiculous restrictions aside, though, the doors are now open for gay men in civil partnerships to become bishops, less than ten years after the debate even started with the resignation of Jeffrey John as Bishop of Reading.

Finally of course, the Church and the government are setting themselves/each other up for a headache of epic proportions when marriage equality becomes law.

Which, to be honest, would all be perfectly fine if the Church of England’s antics could all simply be filed under “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” and the rest of us could be left to our own devices, as tends to be my standard approach to religion in general. The CofE, however, is a political institution in this country. As the established church, it is intimately intertwined with other institutions of state, from the head of state who is also Supreme Governor of the Church to the 26 seats in the legislature reserved for CofE bishops and thus for men – straight and now gay. And yet while those bishops make our laws, they and the institution they represent continue to be specifically exempt from some of said laws, such as the Equality Act, and they continue to demand further exemptions, as in the case of marriage equality. The rule of law this is not. It is therefore high time that the Church of England was both disestablished and subjected to the laws of the land. In the meantime, let’s hope they don’t really install cameras in people’s bedrooms.

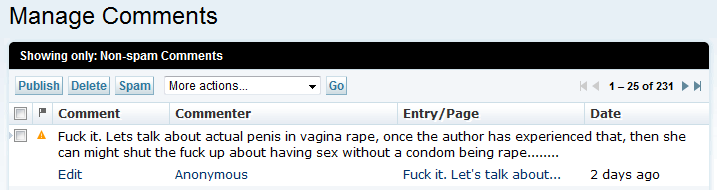

[Trigger warning] Another badge of honour

It was around 1am on Saturday and I was rather inebriated and amongst some of my best friends when the above comment on my post about consent and the Julian Assange case hit my inbox. That perhaps accounts for my complete and utter failure to be upset by it, or take it as anything other than another badge of honour, following in the footsteps of the “fat and ugly” and “fuck off back home” comments that I occasionally receive on this blog and other parts of the Internet. We even had a dramatic reading!

The tragic reality, however, is that this is not even par for the course for women online – it’s remarkably mild and restrained compared to the kinds of things hurled at people like Anita Sarkeesian, Helen Lewis, or anyone who dares to play video games while female. Anonymous is not threatening to harm me directly, or even encouraging others to do so – merely speaking in hypotheticals, surmising that I may change my mind if I was subjected to what they regard as “proper” rape. Bless their little cotton socks, Anonymous cannot even imagine that I may already have experienced sexual assault and that my opinions may be coloured by that experience.

Statistically speaking, of course dear Anonymous, I am about as likely as not to have experienced a major incident of gender-based violence such as sexual assault (including, as you so eloquently put it, “penis in vagina rape”), domestic violence, or stalking. You on the other hand Anonymous, being almost certainly male, rather lack the frame of reference to even begin to imagine what it’s like to live in a world where everyone thinks they’re entitled to a piece of you. The fact that you feel entitled to make this kind of comment to me rather proves this point, but to be honest I don’t actually expect you to understand that – or spot irony if it bit you in arse for that matter.

When I asked Twitter for ideas on what to do with my thinly-veiled rape threat, a number of people suggested I report it to the police and get it traced (it did come with an IP address and what looks remarkably like a real email address). I must admit this had not occurred to me – partly because the comment is, after all, comparatively mild and does not constitute a direct threat; and partly because the bit of me that’s a digital rights activist really does not want to see restrictions on free speech and people arrested and jailed for mouthing off on the Internet. We have already had way too much of this kind of thing recently.

So I am putting it up here instead. I am doing this to raise awareness of the kind of harassment women experience online and the epidemic levels of gender-based violence in our society, but also as an intellectual exercise for digital rights folk. Or as @graphiclunarkid put it, “If you choose to publish a held-for-moderation threat against yourself are you guilty of s127 menacing, um, yourself?!”

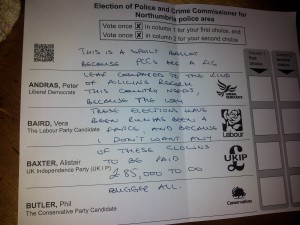

Let’s go spoil some ballots!

Tomorrow (today, depending on exactly when you’re reading this), I want you to go out, find your local polling station for the Police and Crime Commissioner elections and spoil your ballot.

Police and crime WHAT?

Quite. Apparently only just under two thirds of us are even aware these elections are happening. The vast majority of us have not heard a single squeak from the so-called candidates.

To recap for the remaining one third, 41 elected “Police and Crime Commissioners” will replace the existing Police Authorities in England (except for London where you have the fortune of already having Boris as your de facto PCC) and Wales, all in the name of making the police more accountable. The new PCCs will be paid between £65,000 and £100,000 annually to produce a “Police and Crime Plan” for their policing area, set priorities on how police funding is spent, produce an annual report, and have the power to appoint, suspend and dismiss Chief Constables. As job descriptions go, my interns have more demanding ones for considerably less money.

Okay, but WHY?

Good question. Something to do with “accountability”. And probably “bobbies on the beat”. Everyone likes bobbies on the beat, right? Quite possibly also to facilitate the privatisation of large chunks of the police to companies like G4S; or to party-politicise the police – because that works so well!

Now, don’t get me wrong. Policing in this country needs urgent and extensive reform. Ask the families of the Hillsborough victims. Ask the families of Ian Tomlinson and Jean Charles de Menezes and the 1431 other people who have died in police custody or after contact with the police since 1990. Ask anyone who’s been charged at by the Met’s finest on horseback. Ask the rape victims whose investigations were botched and deliberately obstructed by the police. And ask Steve Messham.

But let’s be clear: Electing John Prescott and the like to produce some glorified pieces of toilet paper is not going to achieve the kind of reform we so badly need. And let’s be clear on something else too: Theresa May does not want you to vote in these elections.

Theresa May doesn’t want me to vote?

The Electoral Reform Society estimates that due to a number of factors – all within Mrs May’s control – turnout at these elections is likely to be a record low, somewhere around the 20% mark. Theresa May continues to cheerfully insist that that doesn’t matter and whoever is elected will have a democratic mandate.

If Theresa May wanted to you vote, here are a few things she could have done:

- Scheduled the elections to coincide with other, more established elections, e.g. local ones, and not in winter.

- Had information about the elections and the candidates mailed out to you.

- Provided information not just online (excluding 7 million registered voters who do not regularly access the internet), and provided information in accessible formats for the disabled.

- Encouraged independent candidates, rather than shafting them by excluding anyone with any kind of previous conviction, demanding a £5,000 deposit and denying them a free mailshot to voters.

She has done none of these things. Theresa May definitely does not want you to vote.

I don’t want to do what Theresa May wants me to, but these elections are pointless and counterproductive. What do I do?

Whatever you do, don’t do nothing! It plays into the hands of the government. It plays into the hands of extremists candidates. It encourages politicians to keep disregarding you.

You can, if you want to, vote. If you live in a policing area where there are extremist candidates and you feel they are likely to win, then by all means do vote for the lesser evil.

If you want to be annoying and obstructive (and I don’t blame you if you do), you can pocket the ballot paper. It causes all sorts of havoc if a ballot paper has been issued but doesn’t end up in the ballot box. This does carry some risk and I’m told you may get chased down the street by the returning officer. For a slightly safer though lesser level of havoc, you can write “CANCELLED” on your ballot paper and put it in the ballot box.

My preferred option is spoiling your ballot. This makes it clear that you care, and you have bothered to turn up, but also that you do not feel that these elections are legitimate or that any of the candidates deserve your support. Imagine the signal we would send if the election was “won” by spoilt ballots. The other good reason to do this has to do with the candidates’ deposits. As I mentioned above, the deposit is £5,000, and candidates only get it back if they receive at least 5% of the votes cast. Again, imagine the message we would send if even the successful candidate lost their deposit because they were elected on less than 5% of the votes cast, at a turnout of 20%!

How to spoil a ballot

A final thought on the finer points of spoiling your ballot. From my experience as a counting agent at the AV referendum, the Electoral Commission produces guidelines to ensure that as many ballots are counted as valid whilst being interpreted correctly as humanly possible. (Note: Returning officers do not always read these guidelines. Counting agents generally will, and will fight for every ballot they can possibly imagine going their way.) Combine this with this being the first use of the supplementary vote system outside of London Mayoral elections, and I think you really can’t afford to be subtle about spoiling your ballot. Don’t play around with writing numbers in the boxes, ranking your candidates, putting in ticks instead of crosses, etc. Write something on your ballot that makes it very clear that your intention is to spoil it. One suggestion is “No to police commissioners, yes to democracy”. “This is a spoilt ballot” will do just as well. Just don’t give people any chance of counting your ballot as valid unless you want them to.

Happy ballot-spoiling!

Join the Open Rights Group today to help protect *your* digital rights

A quick reminder from me as to why everyone should care about digital rights:

Digital rights are human rights – they go beyond the technorati.

Parents get advice and support on all kinds of issues on Mumsnet. Feminists organise through websites like The F Word which often translate into real world action. Disabled people find new ways of reaching out to the world and fighting for their rights through The Broken of Britain Campaign. Bullied lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender teens can find new hope through the It Gets Better videos. Men, women, black, white, straight, gay, Muslim or humanist, able-bodied or not, the internet brings us together and empowers us all.

At the same time, this new-found empowerment is under constant threat. Copyright lobbyists are demanding powers to censor free speech and disconnect us from the internet without due process. Politicians threaten us with the Great Porn Firewall of Britain, potentially preventing vulnerable LGBT teenagers from accessing information and safe spaces online that may help them come to terms with their sexual orientation and even save their lives. People are taken to court for posting messages on Twitter and Facebook. The security services want to know where you’ve been, who you’ve been talking to, and what websites you’ve visited.

As the information war gains new fronts almost on a daily basis, it is vital for all of us to be engaged in what is perhaps the defining political issue of the 21st century.

And now we interrupt your regular schedule for a special announcement from the Open Rights Group:

After a year of successes ORG is ready to take the next step in the battle for your rights!

We campaigned for change to copyright that would create a new right to parody, built the coalition against the Snoopers’ Charter, broke the story of Mobile Internet censorship, and our hard work against ACTA came into fruition as we watched MEPs shoot down a law that would have led to damaging copyright policy. We couldn’t have done any of it without our supporters!

ORG is now prepared to take legal action to challenge threats to your digital rights.

We now need to fund a new position: a legal expert who can co-ordinate our crack-team of volunteer lawyers, perform thorough legal research, and create new case law to actively prevent potential threats to civil liberties.

You can help ORG achieve this! We only need 150 new members to start our legal project; 300 new members could pay a Legal Officer full time. Join the Open Rights Group today to help protect your digital rights!

[Elsewhere] Ada Lovelace Day: A Celebration

Back in April this year, the Guardian published its “Open 20” – a list of twenty “fighters for internet freedom”. As with any such list, the opportunities for criticism and disagreement are endless. What struck me in particular, though, is that not only does the list contain just four women but one of them is Ada Lovelace. As illustrious and pioneering a woman as the Countess of Lovelace was, she died in 1852, over a hundred years before anything that can be legitimately seen as a progenitor of the internet, and thus can hardly be described as a fighter for internet freedom. You know we’re struggling to showcase female participation in a field when we have to scrape the barrel for examples from before the field even existed.

Read more on ORGZine.

[Ada Lovelace Day] Finally, my mother…

Today is Ada Lovelace Day. Today we blog about great women in science, engineering, technology and maths – women who have inspired us, women who can act as role models to a whole generation of girls and show them that a successful career in a male-dominated area is not only possible but also fulfilling. Today is when I tell you about my mother.

My mother was born in the 1950s and grew up in Communist Bulgaria. She wanted to be a doctor. At the time, trainee doctors were shipped off all over the country, and you had no control over where you would be sent – my grandparents were not happy about this, and as far as I know the story, my grandfather put his foot down and told my mother that she wasn’t allowed to study medicine. They made a deal: if she agreed to study something more acceptable, like chemistry, he would enable her to go on exchange to Moscow. My mother kept her end of the bargain but for reasons I don’t know she never went to Moscow.

Once she graduated, my mother had a successful, decade-long career as a research chemist. She had specialised in organic chemistry and surfactants – things that you find, for instance, in washing powder. What she actually worked on were better, foam-based fire extinguishing chemicals.

Fairly early on in her career, my mother decided to have me. She got married at 23 and had me when she was 25. In some ways, having children young was easier in Communist Bulgaria. Maternity leave provisions were extremely generous with a paid period and up to three years unpaid. Childcare was affordable and pretty much universally available. In some ways, it was tougher – my parents lived with my grandparents until I was four years old.

My mother wanted to put me in nursery when I was six months old and return to work. I’m afraid I was having none of it, and in the end, she took the full three-year maternity leave. I’m not sure I can really regret something I did when I was six months old, but this one I do. Once she did return to work, she continued to work on fire extinguishing foams, and her career progressed pretty well.

I have a very vivid memory – I must have been eight or nine – of my mother taking me into work. It may have been during the school holidays, or school may have been closed for some reason – I’m not sure. I got to watch one of her experiments – I got to watch her set things on fire! That was exciting! Very shortly after that, like so many women in so many different circumstances, my mother sacrificed her career for our family.

When Communism collapsed in 1989, things took a turn for the worse very quickly. By early 1990, there was quite literally no food. There was food rationing. I remember booklets of yellow vouchers – this many for sugar, that many for flour, that many for oil. I remember – aged nine – fighting in a supermarket with a middle-aged woman over a bar of soap. I remember one bitterly cold January day standing with my mother in a queue at the butcher’s only to watch as they ran out of everything just before it was our turn. The butcher had put aside some meat for his own family, and when he saw me, he decided to share it with us. By mid-1990, my father had decided that we were leaving the country.

How exactly we ended up in Austria is a different story entirely, but while my father was fluent in German, neither my mother nor I spoke a word. I was thrown in at the deep end, sent to school, and within a few months, I was fluent. My mother had a much tougher deal. While I was at school and my father was at work, she was home alone with a pile of textbooks. She didn’t have the confidence, nor really the opportunity, to go out and speak. On top of that, my father insisted that at home we spoke Bulgarian – and while in the long run that was the right decision for me and the whole family, in the short run it made my mother’s life even more difficult.

By the time my mother’s German was good enough to work and she managed to wrangle a work permit, she’d been out of chemistry for four years. She was in a foreign country which hardly had any industry at all – certainly not in the part of the country where we were – and had very little of a social network. Would she have liked to return to science? I think so, but I don’t know for certain. In the end, though, she looked at which of her skills she could market and began first to teach German to refugees from the various Yugoslav wars and then to translate for an insurance company. She has changed career twice since then and now works in back office in an investment bank.

Here are some of the things my mother taught me:

Women work. For as long as I remember, my mother has had a job and most of the time a career. The short periods between jobs or careers were the times when she was truly miserable. She always wanted to work. There were – as far as I’m aware – never any questions about “having it all”, about combining motherhood with a career. My father pulled his weight around the house, and my mother worked outside the home. This was normality. I distinctly remember, when we moved to Austria, finding out that there were women who were “housewives”. I did not understand that concept. Women worked.

Not only do women work, but women can be anything they like. My mother was a research chemist, after all. When I was still in kindergarten, I actually thought she was a firefighter, because she worked in the research division of the national fire service. When I told the other kids this, they told me that women couldn’t be firefighters. I never believed it for a second – my mother was one, after all. When I was growing up and considering various career options, at no point did I ever think “I can’t do that because I’m a woman” or “It’ll be more difficult for me to do that because I’m a woman”.

These two very basic assumptions – that women work and that women can do whatever they like – are incredibly deeply ingrained in my approach to life. They give me what I’m sure looks from the outside like a huge sense of entitlement: as long as I work hard and bring the right skills to the table, I have a right to be in any workplace and any profession I choose. Yet this sense of entitlement is tempered by the third thing that my mother taught me – that sometimes we have to make choices and adapt.

In her fifties now and on her fourth career, my mother’s done her fair share of adapting. She’s adapted to changing priorities, to external catastrophes, to circumstances beyond her control. It is that adaptation that for me has enabled those first two basic assumptions to survive contact with western capitalist society. I’m nothing like as good at this as my mother – or possibly my priorities lie elsewhere and I have made different choices – but I greatly admire her for it, and for everything else she’s achieved.

Nothing to hide

Imagine the government had the power to compel your internet service provider, your mobile operator, or even Google and Facebook to collect or retain certain data about your activities: who you were talking to, when and how long for; where your mobile phone was at a given time; what websites you visited. The police could then use this data to scan for suspicious activity, or trace an individual suspect’s activities through the entirety of their electronic life.

This is precisely what the government is proposing in the Draft Communications Data Bill. While some data is already being retained for a limited time period with the intention of being able to reconstruct a suspect’s activity for criminal investigation purposes, the new proposals go several steps further. They include the creation of entirely new data sets and the powers to “data mine” – investigate the data for conspicuous patterns even if no crime has been committed.

Sure, you say. I’m not a suspect; I’ve got nothing to hide. If it helps the police catch terrorists and paedophiles, why not?

Are you sure you have nothing to hide? Who decides what activity is suspicious, and what action to take as a result? Think about it.

Let’s say you’re an investigative journalist – or simply someone who likes the idea of investigative journalists being able to do their jobs and expose shady dealings and dodgy expense claims. You’re the kind of investigative journalist who meets contacts at random times in random places, who gets anonymous tip-offs, who works on stories that can be extremely embarrassing to the government… or the police. Even if your activity hasn’t already been singled out for analysis, chances are a high level scan would throw you up as someone who is suspicious. Who are you meeting in the middle of the night in a deserted car park? The police only need to look up who the other mobile phone in that car park belongs to, and they know. Who have you been emailing? What have you been googling? Suddenly a picture begins to emerge of the story you’re working on.

Oh, and by the way… your mobile phone was located at your GP’s surgery three times this month; or at the abortion clinic last week; or at the AA meeting. While the police may not necessarily want to know that, there are plenty of people who do: you employer, your church, or if you happen to have the misfortune to have attracted public interest in some way, the Daily Mail. Have we really seen the end of phone hacking, blagging and all the other dirty tricks that went with them in the tabloid press? Just by existing, the enormous data set the government is proposing to create becomes a target for all sorts of malicious activity.

It’s not like police don’t already abuse existing data either. With access to location information or detailed data on who someone has been communicating with, corrupt police officers get even more leverage over their victims. Domestic violence victims may well initiate contact with their abuser as part of the pattern of abuse they suffer. If the copper investigating your case has that information they can blackmail you into all sorts of things with the threat that it will be used to “prove” that you aren’t a victim of domestic violence after all.

Call me paranoid, but before handing additional powers to the state, I would like them to pass the “Stross Test”. This is based on a short story called “Minutes of the Labour Party Conference 2016” by Charles Stross, published in the anthology “Glorifying Terrorism”. In the story a BNP government uses anti-terrorism legislation passed by Labour in 2006 to establish and uphold a fascist state by labelling all opposition, including the Labour Party, as terrorists. Would you trust the BNP with the Draft Communications Data Bill?

The Open Rights Group is currently campaigning against the Bill. You can use the ORG campaign website to email your MP and explain to them your concerns about the proportionality, the potential for abuses and the lack of proper safeguards of these proposals.

In the meantime, with party conference season upon us, I will leave you with this thought from the minutes of that fictional Labour Party Conference in 2016:

“The Party would be grateful if you can reproduce and distribute this document to sympathizers and members. Use only a typewriter, embossing print set, mimeograph, or photographic film to distribute this document. Paper should be purchased anonymously and microwaved for at least 30 seconds prior to use to destroy RFID tags. Do not, under any circumstances, enter or copy the text in a computer, word processor, photocopier, scanner, mobile phone, or digital camera. This is for your personal safety.”

Changing our attitude

David Cameron hopes that the Paralympics will change our attitudes to disability. In the interview he gave to Channel 4’s Alex Brooker just before the opening ceremony (which I cannot for the life of me find a clip of), the Prime Minister said that he wanted us all to focus on what was possible rather than what was impossible with regards to disability. A laudable aim? Not necessarily, when you consider his government’s record on disability.

The government’s policy of cutting benefits and trying to move more disabled people into work has been a miserable failure. Hundreds of people died last year after being declared “fit to work” by Paralympics sponsor ATOS, while over 50,000 people (over one third of all claimants delcared fit for work) have had their Work Capability Assessment overturned on appeal. Yet by framing the Paralympics in the narrative of “what is possible” David Cameron continues to steer us all down the line of believing that there are only two options for the disabled: be a Paralympic athlete or be a benefits scrounger.

Having spent the last two weeks watching disabled people break world records and achieve the seemingly impossible, we can perhaps be forgiven for falling for the “what is possible” narrative. We have, after all, acquired a whole host of new heroes: Ellie Simmonds, Alex Zanardi, Kylie Grimes, Sarah Storey, Johnny Peacock, Hannah Cockroft, David Weir, Terezinha Guilhermina have all become household names synonymous with courage and perseverance in the face of adversity. It is a hugely empowering story for the disabled and able-bodied alike. Arguably though, it is not the full story, and the question we should be asking is not “what is possible” but “how is it possible”.

Throughout the Paralympics, we have seen glimpses of where the narrative breaks down. We saw Mirjam de Koning-Peper not start at the S6 100m freestyle because her condition – which is variable – had deteriorated. We heard athletes thank a dozen people – coaches, physios, funders – who have supported them and enabled them to get to where they are. We saw Ade Adepitan demonstrate how he could actually turn his wheelchair in the bathrooms in the Paralympic village – the first Paralympic village with that particular feature! We saw, albeit briefly and only on Channel 4’s brilliant The Last Leg, armless athletes struggle to get out of an Olympic swimming pool with no ramps. No matter how much courage and perseverance you have, individual achievement does not happen in isolation.

Unfortunately, we still live in a society where the odds are overwhelmingly stacked against disabled people. With the government’s sustained two-year campaign of painting anyone on any kind of benefits as a scrounger, we have seen disability hate crime soar. People are having their benefits taken away, being declared fit to work in an economy with an unemployment rate of 8% and with no support to help them make a successful transition into work. They are being put through extremely stressful assessments which often exacerbate their conditions. By all means, our attitudes to disability should change – but the first people to change their attitude should be David Cameron and his cabinet.

Yet we have also seen how the right support and the right investment can enable anyone to achieve their full potential. Lottery funding and the rare corporate sponsorship have enabled athletes like Hannah Cockroft to shine. Channel 4 has invested £600,000 in training and developing their amazing team of disabled presenters. In these rare and exceptional cases where we have bothered to create an even playing field, we have managed to all but obliterate the boundaries between the disabled and the (temporarily) able-bodied. Yet that takes time, it takes investment and dedication from all of us as a society. Can we all commit to doing that? Can you, Mr Cameron?

Response to DfE Consultation on Parental Internet Controls

The Department for Education’s consultation on parental internet controls (aka the Great Porn Firewall of Britain) closes tomorrow (that’s Thursday, September 6th). For those of you who’ve not been following this one, this is the proposal to make ISPs block pornography unless you specifically ask them not to. It’s one of those ill-thought-out “think of the children!” initiatives which make it look like the government is doing something while being both utterly ineffective and actively harmful.

The Open Rights Group has a campaign page which makes it easy for you to tell the government precisely what you think of the Great Porn Firewall of Britain, and even if you only write two sentences, I would still strongly encourage you to head over there and submit a consultation response before close of business on Thursday. If you need inspiration, mine’s below:

My response to the Department for Education Consultation on Parental Internet Controls

A copy of this email is going to my MP. I am raising my concerns about the proposal for network filtering of adult content and default blocking.

I would like to submit the following evidence:

The proposals for default blocking of certain content are ostensibly there to make it easier for parents to restrict their children’s access to online pornography. Yet this is a blanket measure which will in one way or another affect all 26 million households in the UK. According the government’s own data only 7.5 million of those households actually have dependent children living in them. This is clearly a vastly disproportionate measure.

Additionally, such mechanisms are unlikely to actually work, either at the micro and at the macro level. From an individual household’s point of view, blocking content at the point of internet connection ignores the fact that different members of the household have different content needs. Content filters also have a tendency to not be very effective at blocking the kind of content they are targeted at, while also often blocking content which is harmless.

The proposals are of particular concern to the LGBT community as simple information about different sexualities can often be blocked by such filters. For children and teenagers growing up and beginning to question their sexuality in an environment which is often still hostile, lacks positive role models and where bullying is rife, the internet can often be a lifeline to finding more information, talking about one’s experiences and finding a more accepting community. The blocking proposals put this lifeline at risk and thereby put children at risk.

Finally, blocking as proposed at the internet connection level is open to future misuse and abuse and opens the door to censorship of other material without adequate justification or oversight.

[Elsewhere] Three things I learned at the Turing Festival

Governments are not in the business of defending freedom

To seasoned digital rights campaigners this is probably not news, but it’s definitely something worth reminding ourselves of. It was certainly a theme that ran through the “Freedom and Security” session at the Turing Festival in Edinburgh on Saturday morning.

Read more over on ORGZine.