For the sake of completeness, I’m quoted in this Guardian piece on bisexual issues in the workplace.

The Snoopers’ Charter is back. With a Vengeance.

The perceived trade-off between freedom and security has been a defining feature of the early 21st century. With “terrorists” allegedly lurking around every corner, a number of governments, including successive UK ones, seem to have taken a “legislate first and ask questions later” approach. Add to this the revolutionary effect of digital technology and the Internet in particular on the relationship between the state and the individual, and worrying trends begin to emerge.

In the US, the Patriot Act gives authorities the power to, for instance, demand that individuals and organisations hand over vast amounts of communications and transactional data, while at the same time prohibiting anyone receiving such a demand from speaking about it. Statistically, between 2003 and 2006 one in every 1500 Americans received such a demand. In the UK, the Terrorism Act of 2006 prohibits something it vaguely calls “glorifying terrorism”, while the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) – also originally intended for use against serious crime and terrorism – allows councils to spy on people suspected of breaking the smoking ban.

The Draft Communications Data Bill, which was last year shredded by a Joint Select Committee and yet is about to make it back onto the government’s legislative agenda, proposes to significantly extend existing police powers to monitor our digital lives. If passed into law, the proposals would allow the government to compel telecommunications operators – anyone from Royal Mail, Internet Service Providers and mobile operators to Google and Facebook – to retain and collect transactional data on their users: who they spoke to or emailed and when, where they were based on their mobile phone location, even which websites they visited. While some data is already being retained for a limited time period with the intention of being able to reconstruct a suspect’s activity for criminal investigation purposes, the new proposals go several steps further. They include the creation of entirely new data sets and the powers to “data mine” – investigate the data for conspicuous patterns even if no crime has been committed.

Given well-documented abuses of existing powers and legislation, civil liberties and digital rights campaigners like the Open Rights Group are raising a number of concerns about the Draft Communications Data Bill. The potential for abuse of such powers – both by those authorised to access the data but also by malicious individuals for whom the simple existence of such a data set is a target – is staggering. Even without knowledge of which websites someone has visited – which automatically gives you access to the content they have accessed – it is remarkably simple to make conclusions about the content of a conversation by cross-referencing different pieces of information such as where an event took place, who was there, or the time of day when it occurred.

In some ways, however, the problem with the Draft Communications Data Bill is not so much the potential for extreme abuses of these powers – though that too is a concern. Rather, this is another step in a gradual but fundamental shift in the relationship between the state and the individual. Digital communication has given individuals unprecedented freedom to associate, exchange ideas and power to hold governments to account. At the same time, digital data processing creates the potential for government to spy on our every move. Never before – not even in totalitarian states like the Soviet Union and East Germany – has the state had the power to map and examine individuals’ lives with such a level of detail.

The challenge here is the insidious nature of mass surveillance – the danger that with every new set of powers the state grabs for itself, every restriction on our freedom and civil liberties in the name of some abstract concept of security we just begin to feel that this acceptable, normal, expected. Just as we hardly notice CCTV cameras anymore – we just assume they are there – will we in future assume that a database is storing our every move, a computer analysing all the data and flagging up when we walk out of line?

We need to start asking the questions and having the conversations before legislating. We need to ask ourselves if we want a state where the police and security services have the power to spy on all of us. Who benefits from such powers and who loses? If we do want to give the state such powers, what safeguards should we put in place and what governance structures? These are debates that we as a society are currently largely failing to have. The Open Rights Group’s campaign against the Communications Data Bill is a good starting point. Write to your MP. Join the debate.

In memory of Margaret Thatcher

I wasn’t in the UK when Margaret Thatcher’s policies wrecked this country and sowed the seeds of many of the problems we are facing today; which is not to say that the Iron Lady’s reach did not extend beyond the Iron Curtain. I was slightly taken aback by Angela Merkel’s praise for Thatcher who, in Merkel’s words, “recognised the power of the freedom movements of Eastern Europe early on and lent them her support”; until of course I remembered that as an East German Merkel’s experience of the fall of the Iron Curtain would have been very different to mine.

West Germans to this day pay the Solidaritaetszuschlag – a tax earmarked for the economic development of East Germany. Where East Germany saw a rise in unemployment, Bulgaria and other countries of the Eastern Bloc saw complete economic collapse. State assets were stolen by those in power or sold off to the highest bidder. As a nine-year-old I fought grown-ups in the supermarket over a bar of soap. I did my homework by candle light or scheduled it around the timetabled blackouts. I stood in endless queues for bread and meat, only to watch as they ran out before I got to the front. Even after we left I watched friends and relatives have to make choices between heating their homes and eating, as their money got so devalued it was only good for burning anyway.

No, the fall of the Iron Curtain wasn’t all velvet revolutions, sunshine and rainbows. While in the long run even countries like Bulgaria may find true democracy and prosperity, it’s been over 20 years now, and we’re still not there. The supremacy of the market advocated by the likes of Margaret Thatcher is maybe not the sole cause of Bulgaria’s continued misery, but it’s certainly a factor.

So while I wasn’t here when Thatcher was in power, I am hardly untouched by her policies. And more to the point, I am here now, and her legacy is still very much alive. I am not celebrating Thatcher’s death, nor am I passing judgment on those who are. But I am hoping to make a small contribution to the death of her legacy. Prompted by this, I am therefore going to donate money to four charities tomorrow, in memory of Margaret Thatcher.

Newcastle Women’s Aid

I live in the Northeast, an area with a proud mining heritage brought to its knees by Thatcher’s policies. The current government’s cuts are also hitting the region disproportionately, and a worsening of economic conditions often brings with it an increase in domestic violence and abuse. At the same time, the government is cutting funding for domestic violence services, putting thousands of women and children and risk. My first donation is therefore going to Newcastle Women’s Aid in the hope of easing the suffering of some of those affected by the cuts locally.

Terrence Higgins Trust

Given Thatcher’s treatment of the LGBT community, it is important to me that some of the money donated in her memory should go towards some of the damage done to that community. The Terrence Higgins Trust is not an LGBT-specific charity; but given the disproportionate impact of HIV on the LGBT community, vastly exacerbated by policies like Section 28, I feel it is a cause worthy of support.

Broken Rainbow

Silencing the LGBT community has unfortunately also exacerbated domestic abuse issues within it. When teachers are not allowed to talk about the kind of relationship you might be in, when service providers refuse to acknowledge that the person who beat you black and blue was of the same sex as you, when an opposite-sex partner has the power to out you as bisexual in a society that won’t accept you, when as late as the early 2000s you had no legal way of getting your gender recognised and even today you can only do so with your spouse’s consent, the whole community suffers. Broken Rainbow, of which I am a trustee, does vital work as the only national LGBT domestic abuse helpline and will also be receiving a donation in memory of Margaret Thatcher tomorrow.

Brook

Finally, Brook, the young people’s sexual health charity, will also be receiving some of my money. This government is trying to take sex and relationships education back to the 1950s, trying to do to the young people of today what Section 28 did to the young LGBT people of the 1980s and 1990s, all while Michael Gove sniggers like a 12-year-old behind the bike sheds. Not on my watch.

While our government spends £10 million on the woman who thought there was no such thing as society, let’s all show them what society looks like; and let’s remember, come 2015, what they chose to spend our money on, and what we would choose to spend it on.

Not talking about Thatcher

I wasn’t going to talk about Thatcher, but the Daily Mail today is treating us to a spectacular trainwreck of a headline: “‘They danced in the streets when Hitler died too’: Drama teacher who organised Thatcher death parties remains unrepentant as it’s revealed she had NHS breast implants”

To which, I must admit, my first reaction was “Surely Maggie could afford to go private”.

If Daily Mail editors read more material that involved long passages of exposition talking about two people of the same gender (slash fiction for instance), they would be aware of the pitfalls of connecting the wrong subject with the wrong predicate in a sentence. Frivolity aside, though, it strikes me that this particular crash blossom is more likely to have its roots in our culture’s assumptions about who holds power rather than in the dubious reading habits of Daily Mail staff.

As a former Conservative Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher may have had the “body of a weak, feeble woman”, but I rather suspect that in the minds of the Tory faithful she had “the heart and stomach of a king”. I’m not sure it even occurred to the poor sod who wrote that headline for the Mail that Thatcher, too, had breasts.

I may be reading too much into this, but I do think it illustrates quite nicely that for many in our society those in power and those with female bodies are still two very separate groups of people.

When is International Men’s Day?

When you ask me the above question, here’s what I hear:

- I think I am funny and original. I live in a bubble so privileged and sheltered from the real world that I cannot even imagine that at eight o’clock in the morning on March 8th I’m not even the first person to ask you that question.

- Despite this International Women’s Day clearly being a thing, I have never even given a single thought to why it might be a thing; why people feel there may be a need for it; how women’s lives are different to my own little bubble of privilege.

- On a day deliberately designated for the celebration of diversity and inclusion, I can’t be bothered to take a second to think about whether my behaviour and comments are inclusive, or within the spirit of that day. Let’s not even talk about all the other days of the year.

When you ask me the above question, here’s how it might make me and others around us feel:

- Dismissed and trivialised. It’s bad enough that there were cupcakes involved.

- Put on the spot. I can either stand up to you and be a role model to those around me, at the price of some significant personal discomfort, or I can not look in the mirror for the rest of the day. Either option will upset me sufficiently to distract me from doing my job.

- Disappointed. Because really, you should know better, and there is no way in hell that I should have to deal with this.

And when I finally answer the above question, here are some things you maybe shouldn’t do:

- Be surprised that I spoke up for myself.

- Look at me like I just kicked your puppy for telling you that “That’d be all the other days of the year.”

- Tell me you don’t think that’s quite true.

Just some food for thought.

[Elsewhere] Digital Colonialism: Africa’s new communication dimension

Africa is rapidly becoming “the place to be” for Western businesses. Despite common preconceptions expressed in Twitter hashtags like #FirstWorldProblems, a lot of African economies are growing rapidly, and US and European companies are looking to the continent for their next wave of consumers. This is not as surprising as you might initially think. Compared to Western Europe with its declining birth rates and, in many countries, negative population growth, Africa’s population continues to grow rapidly.

Read more on OrgZine.

The ORGZine link seems to have broken some time during the re-design. I am therefore including the full article below.

Digital Colonialism: Africa’s new communication dimension

Africa is rapidly becoming “the place to be” for Western businesses. Despite common preconceptions expressed in Twitter hashtags like #FirstWorldProblems, a lot of African economies are growing rapidly, and US and European companies are looking to the continent for their next wave of consumers. This is not as surprising as you might initially think.

Compared to Western Europe with its declining birth rates and in many countries negative population growth, African population continues to grow rapidly. Nigeria alone has more babies than all of Western Europe put together, while life expectancy across the continent is increasing. The population of Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to rise by nearly 40% to over 1 billion by 2025. Real GDP growth for Sub-Saharan Africa is projected to be around the 4.5-5% mark for the rest of the decade; and while this is not quite the double-digit growth of the Asian Tigers in the 1990s, it’s a rate that countries like the UK can only dream of right now.

Technology plays a key part in Africa’s growth. Some time this quarter, mobile phone penetration on the continent is projected to exceed 80%, and with Airtel having just successfully completed a 4G/LTE trial I wouldn’t be surprised if Nigeria soon had better 4G coverage than the UK. Mobile banking is far more successful in Africa than it has been in many Western countries. Mobile phones are even used in pilot projects to improve cervical screening in Tanzania.

In a high-population, rapid-growth setting with advanced technological capability and infrastructure, it should come as no surprise then that intellectual property is also rapidly becoming a hot topic in the region. The African Union proposal for a Pan-African Intellectual Property Organisation (PAIPO) started gathering momentum in the final three months of last year, raising a lot of concerns in the process. The objectives of the proposed organisation as listed in the draft statute include among other things:

- Ensure the effective use of the intellectual property system as a tool for economic, cultural, social and technological development of the continent;

- Promote the harmonization of intellectual property systems of its Member States, with particular regard to protection, exploitation, commercialization and enforcement of intellectual property rights;

- Initiate activities that strengthen the human, financial and technical capacity of Member States to maximize the benefits of the intellectual property system to improve public health and eradicate the scourge of piracy and counterfeits on the continent; and

- To foster and undertake positive efforts designed to raise awareness on intellectual property in Africa and to encourage the creation of a knowledge-based and innovative society as well as the importance of creative industries including, in particular, cultural and artistic industries

A tall order if I ever saw one, and many commentators in and outside Africa are rightly questioning whether the copyright maximalism that clearly underlies these proposals is the right way to achieve any of these goals. There is a nagging suspicion that this initiative is driven not so much by a concern for the interests of people in Africa as by a desire of Western corporations to have an intellectual property regime which suits their ambitions for the continent. Given that only around 10% of applications for the registration of IP rights in Africa are made by African citizens or residents, that suspicion does seem justified.

Whatever intellectual property regime the African Union settles on will have a profound impact on the whole continent and its people. As well digital technology, IP regulations have implications for food security, access to affordable medicine, as well as access to knowledge and educational resources – all areas deeply relevant to Africa’s social and economic development.

The PAIPO draft statute has been criticised for lacking subtlety and nuance, advocating a “one size fits all” approach to intellectual property. The calls for harmonisation of African IP laws are a definite cause for concern. If intellectual property is to be viewed as a tool for development rather than an end in itself imposed from outside, it is clear that a differentiation of IP regimes is appropriate between countries as diverse as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Libya, South Africa or South Sudan. There is also a lack of clarity on the proposed new body’s relationship with existing African IP organisations, as well as with African efforts within the wider WIPO framework. Arguably, scarce resources would be wasted on creating a third African IP body for the convenience of Western businesses and would be much better spent in encouraging the emergence of local creative and knowledge economies.

The public discourse around the PAIPO proposals resulted in a petition ahead of the 5th African Union Conference of Ministers of Science and Technology in Brazzaville, Congo, in November last year, calling for an urgent rethink around IP frameworks in Africa. As Dr. Caroline Ncube, IP scolar at the University of Cape Town, points out, the outcome of this meeting is unclear, but it is likely that for now at least the current draft statute is on ice. Will it come back in a different form? Probably. Let’s hope that when it does, at least some of the key issues and concerns have been addressed.

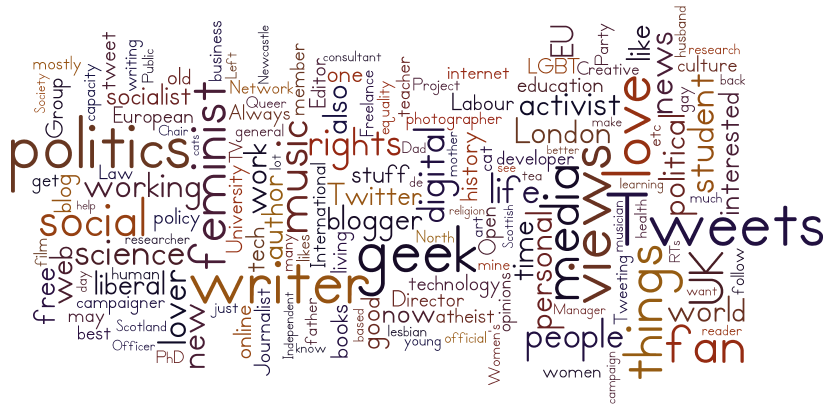

Twitter word cloud

Last week, the Abortion Support Network ran a fundraising initiative promising the first ten people to donate £10 a wordcloud based on their tweets, made by @geoffsshorts. I don’t know if you can still get them, but you should donate to ASN regardless. My word cloud is below. I’m honestly not sure what it says about me…

The future is here and it is disappointing

Let’s be clear on one thing here: we have the technology. We have the technology for me to be able to view any piece of digital video ever made, instantly, wherever I want, whenever I want. And another thing: I have absolutely no objection to paying for viewing said digital video; but I do object to so-called content providers taking the piss.

Case in point: LoveFilm vs Netflix

I’ve been meaning to try out both LoveFilm and Netflix for a while. I got doorstepped by a very cold lass from LoveFilm last week, and I took pity on her and said yes to her three months for the price of one trial. Then, for the sake of comparison, tonight I also signed up for the Netflix trial. So far so good – let see how they compare.

Netflix outdoes LoveFilm for sheer creepiness. Once I log in on the PC, it automatically logs me on the PS3. I’m assuming it just uses my IP address to identify me, but it’s creepy as hell.

In terms of content, they both suck in slightly different ways. LoveFilm doesn’t have films which I would expect it to have (but Netflix does), Neflix doesn’t have some TV shows that LoveFilm does. Neither of them has one of the shows I really want to see – or rather, Netflix does, but only in the US.

Perhaps the most ridiculous way in which they both fail is technically. The LoveFilm app on the PS3 crashes any time the network connection slows down. Netflix refuses to work on Linux (but will allegedly work on a Chromebook). Netflix doesn’t seem to have an easily identifiable way to queue things to watch in future. LoveFilm has a vaguely useful Watchlist functionality on the PC interface… which does not seem to be available in the PS3 app. I don’t even. WHAT?

Case in point: The National Hockey League

If you happen to live in the UK and want to watch NHL games now that the lockout is over, you’re screwed. There’s some sort of obscure, paid-for channel on Sky which screens about 10 as far as I can tell random games a week, but that’s about it. The NHL does have its own online streaming service which, however, only works in North America for games which your local TV network won’t show. Now, as much as I do get the value of TV deals to sports organisations like the NHL, making it difficult for your fans to access your product seems somewhat counterproductive to me.

Dear Netflix, LoveFilm, NHL and co.: give me just one good reason not to go to the PirateBay!

And here of course every content provider screams, “We can’t compete with free! We must shut all these naughty file sharing websites down, block them and censor them, we must disconnect file sharers from the Internet!”

Well, I’ve got news for you guys: You’re not competing with free. You’re competing with a service which meets my requirements. I have no problem paying for the things I want to watch, or the music that I want to listen to, or the books I want to read. I do it all the time. But if I’m giving you money, I expect a service that doesn’t take the piss; that doesn’t make it deliberately difficult for me to access the content I want to view; that actually works.

Try harder, chaps.

Mili’s 5-step guide to being a great ally

Following on from last week’s rant about intersectionality and @pozorvlak‘s request for an explanation of solidarity “in operational terms”, I thought it might be a good time to actually write up some thoughts I’ve been having on what makes a great ally.[1] So here’s a five-ish step guide to being a great ally.

Step 0: Can I be an ally?

No matter who you are, you can always be an ally. This is not a role reserved for the ultra-privileged straight, white, middle class man. You can be the proverbial disabled black lesbian [This link will probably make you angry.], and chances are that there is still someone out there for whom things suck harder. That’s what intersectionality is all about, and ultimately that’s what solidarity and being an ally is all about.

Step 1: Check your privilege

If we accept the basic premise of intersectionality – that for some people things suck harder – and we want to do something about it, the first thing we need to do is be aware of our own privilege. This will help us understand the kind of power we have, the kind of power we don’t have, and who we can be an ally to. Being aware of your privilege is not some kind of point-scoring game that you win or lose. It’s an exercise in self-awareness, perspective, and humility.

Here’s an example. I am a member of three oppressed groups: I am female, bisexual and an immigrant. That doesn’t mean that I don’t have a whole bundle of privilege:

- I am white.

- I speak English well enough that few people can actually tell I’m an immigrant from a brief interaction.

- Even as an immigrant, I am an EU citizen so I have the automatic right to live and work in this country.

- I am in a relationship with someone of the opposite gender, so unless I deliberately out myself, I have assumed heterosexual privilege.

- I am quite disgustingly middle class, both in background and in current living standard.

- I am, as Julie Burchill would put it, “educated beyond all common sense and honesty”. (I have an MA in European Politics; some day I may want to do a PhD.)

- Though I’m an atheist, I am culturally Christian in a country that is dominated by cultural and historical Christianity.

- I am in my early thirties.

- I am (for the moment at least) able-bodied.

- I am cisgender.

Every single one of those points has a tangible impact on my day-to-day life that makes things suck less. If you want some concrete examples of how that works, the Invisible Knapsack (white privilege version, sexual orientation and gender identity version, the male privilege version) is a good place to start. It also gives me a certain amount of power and credibility with particular groups of people – it gives me a voice that someone who is not of the same group may not have.

Equally, some of these points also give me huge blind spots in my experience and view of the world. I don’t know what it’s like living as a non-white, or Muslim, or working class, or disabled person. Some areas are bigger blind spots than others. The closer I am to being under-privileged in a category, the more pre-existing knowledge and empathy I will have with people in that category. So even though I am a very privileged immigrant (see points 2 and 3 above) I have a relatively good understanding of what it might be like being a less privileged immigrant.

Checking our privilege allows us to start mapping out the “unknown unknowns” we have in our experience and world view so that we can begin to turn them at least into “known unknowns”. It’s a basic prerequisite for being an ally or showing solidarity.

Step 2: Do no harm

There are lots of ways in which we can do harm or perpetuate oppression, sometimes even with the best intentions. Probably the most common ones are denial, silencing, and dysfunctional rescuing.

Denial

A classic example of denial would be “Why do you need an LGBT group at work? Sexual orientation is not relevant to the workplace.” If you’re finding yourself questioning the validity of someone’s experience because it’s different to yours, you’re probably engaging in denial. This is harmful in several ways. Even if you only engage in denial towards the target group (say, LGBT people) themselves, you are likely to upset people and maybe even cause them to question their own experience which can be very hurtful and counterproductive. If you do this in public, you are actively using the power and platform given to you by your privilege to undermine a target group.

Silencing

“We have bigger problems – we’ll get to yours once we’ve sorted those out”; or, of course, “Transsexuals should cut it out”; or talking of “lesbians and gays” at an explicitly LGB or LGBT event. As someone more privileged you have the power to give a voice to someone else, or to silence them in all sorts of subtle and entirely unsubtle ways. Don’t do it. Just like as, say, a woman you don’t want men to speak for you or silence you, make sure you’re not speaking for or silencing others.

Dysfunctional rescuing

This one is subtle, insidious, and much like the road to hell, paved with good intentions. In a workplace LGBT context, it might be not offering the fantastic job opportunity in Saudi Arabia to the employee you know is gay, without even consulting them. The problem with this kind of “rescuing” is that, while it is indeed well-intentioned, it rarely addresses the real underlying needs of the person or group you are trying to rescue and more often than not it robs them of their own agency.

The thing about doing no harm is that you need to accept that you will get this wrong. None of us is perfect. We will commit microaggressions and sometimes macroaggressions in thought, in words or in actions sometimes on a daily basis. There are a few things you can do to minimise the harm you do with your privilege:

- Become more aware of when you might be causing harm. Think about past experiences where you think you might have got things wrong, and learn from them – don’t repeat the behaviour.

- When you do put your foot in it, and someone calls you out, don’t get defensive. Think about it, apologise, learn from the experience. Yes, this is difficult. I get it wrong all the time. Practice. If you find yourself becoming defensive, think about the “dental hygiene approach to racism” (and other -isms).

- If in doubt, shut up. For more advanced allies who may have someone they can ask, ask. But the minute you begin to doubt whether something is a good idea, put it on ice until you can validate it.

Here’s an example: I’ve been known to use the words “just because I have a uterus” as a convenient shorthand for gender discrimination. Then I started actually paying attention when trans people on Twitter kept saying “penis != man and lack of penis != woman”. Now I’m looking for a different shorthand because my previous lazy phrasing actively excludes and silences trans women and men.

Step 3: Listen!

We’ve already established that our privilege gives us blind spots in our world view, and that those blind spots can cause us to actively harm others and perpetuate oppression. So now that we have some “known unknowns” and we’re at least trying to not do harm, we can move on to turning some of our unknowns into knowns.

There are many ways to do this. If you are a novice at being an ally to a particular group, then just listening to or reading around the current discourse in the field will give you a good grasp of the key issues, the key problems, the needs of the group, the preferred language and terminology. Thanks to the magic of the internet, we live in an age where even the most marginalised groups have ways of at least talking to each other, have a little corner of the world they can call their own where they have a voice. Google will take you to it. Any type of material, from first-person accounts like microaggressions.com to academic research can give you new insights.

Asking people from the target group about their experience is also generally a good idea. However, be aware that they may not want to talk to you about it – now or ever. While I think a lot of people will be happy to answer questions if they are respectfully and sensitively framed, they are under no obligation to educate you. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t get answers the first time – sometimes it’s just not right for a person to share their experiences with an ally. That’s fine – ask someone else, ask when a better time would be, don’t give up on other ways of listening and understanding.

The act of listening and trying to understand will probably lead you to question and discard some of your assumptions – some things you thought you knew. This is a great achievement as it puts you in a position where you are less likely to do harm and more likely to be able to move on to the next step of being a great ally.

Step 4: Use your power for good

The simplest thing you can do with your power, once you have listened and understood the oppressed group, is to be the one dissenting voice among the in-group you are part of. As a straight white man, you have credibility with straight white men that a woman doesn’t. As a cis woman you have credibility with other cis women that a trans woman may not. Use that to challenge prejudice, hateful language or abusive behaviour. Call out sexism, tell your friends that rape jokes are not okay, go to Pride as an ally. Those are all great ways to show solidarity.

Having said that, sometimes it may not be the right time or place to speak out. If your actions or words may put the people you are trying to be an ally to at risk or create an unsafe space for them, then consider staying silent. Also see “Do no harm” above, and this great post on being a feminist ally.

There are other things you can do to be a great ally. The rule of thumb though is that they should always be driven by the needs of the target group. You goal as an ally is to make things suck less for them. Sometimes in the short term that may be through shutting up and not drawing attention to them, while in the long term you want to ensure that you are not part of a silent majority that tolerates or commits oppression.

The more you have listened and understood the target group, the more confident you will be in challenging oppression and doing the right thing as an ally. When I speak out against the government’s rhetoric on immigration – even when as a white, English-speaking EU citizen I technically count as a “good immigrant” – I speak both as an immigrant, but also as an ally of less privileged immigrants. Because of my own experiences, this is a topic I am very confident speaking out on. Ask me to comment on race issues, however, and I’m likely to look around for someone more qualified and point you in their direction. That’s fine too.

Some of the best allies I have worked with will go beyond speaking out. They will proactively look for opportunities to further the target group’s cause and then, in consultation with the target group, go after those opportunities. As well as accomplishing important things, this kind of behaviour can be a huge morale boost to the target group. Knowing that someone believes in you and is likely to put their personal reputation and influence on the line for you is a huge motivator. Allies like that make me work harder for my own cause as well as strive to be a better ally to others.

Step 5: Be prepared to have the difficult conversations

Every once in a while, as an ally you will be in a position where you have a better insight into how to achieve something than the target group. It may be because you have better knowledge of the privileged group, better connections, more influence. Sometimes the right thing for the target group to do may be to take a step back, to take a different approach. Those are difficult conversations to have. They can be incredibly frustrating for the target group, cause a loss of confidence or momentum. They are vitally important conversations to have, and to have respectfully and sensitively.

If you are ever in that situation, make sure that you make your commitment to the target group clear. Sometimes, from the target group point of view, it is difficult to tell whether someone is a genuine ally trying to help or just making the “right” noises while putting obstacles in your way. Make sure there is no doubt about which side you’re on, and make sure to explain why you believe a certain course of action is necessary. If you have built a trusting relationship with the target group, if they have a reason to believe in you, these conversations will be a lot easier. Ultimately, though, also be prepared for your advice to not be taken, and respect that.

As an ally, you may never get beyond step 2 of this process. That is perfectly fine and you’ll be doing a hell of a lot better than many others out there. I would encourage you to at least try step 3 – challenge your own assumptions and preconceptions; you will find it rewarding. How much you speak out and put yourself up as a target in the cause of being an ally is up to you, will vary by situation, and as long as you’ve done your homework with steps 1-3, will be greatly appreciated.

—

[1] Solidarity is a term you are more likely to hear in overtly political left-wing discourse. Ally is a term that is slightly less scary for corporate types. Operationally though there is enough of an overlap between the two concepts that I’m going to use them interchangeably. I do have a slight preference for “ally” not only because of the warm fuzzy feelings it gives corporate types but also because the nature of the word is less abstract and puts responsibility on individuals.

Intersectionality is not rocket science

Did someone declare Transphobia Week without telling me? The torrent of vile hate speech that seems to be making its way around the Internet, from Twitter to normally at least vaguely respectable sites like Comment is Free, started earlier this week with the publication in the New Statesman of an essay by Suzanne Moore on female anger, which contained the ill-advised throw-away line

We are angry with ourselves for not being happier, not being loved properly and not having the ideal body shape – that of a Brazilian transsexual.

What does that even mean?

I watched the ensuing train wreck “live” on Twitter, as Suzanne Moore – instead of taking the high road, saying “Oops, my bad, lazy writing, sorry” and asking her editor to remove the line – degenerated into a veritable tirade of genuinely shocking hate speech. Much though I like some of Moore’s writing, the comments she made were unacceptable to me, and I unfollowed her, expecting – perhaps somewhat naively – that that would be the end of the story.

Of course, the next day Moore went on the offensive in Comment is Free, and the article ended up in my Twitter feed anyway. What got me this time was the following line:

Intersectionality is good in theory, though in practice, it means that no one can speak for anyone else.

If Moore was trying for self-parody, she’s right up there with the Church of England. Before we go on any further though, let me make one thing very very clear: I am a cis woman; Moore’s comments are transphobic; Julie Burchill’s comments, spawned by the reaction to Moore, are also transphobic; they make me feel physically sick.

But let’s talk about that incredibly complex, difficult to grasp, highly theoretical concept that is intersectionality. Stavvers in another similar debate recently put it wonderfully: for some people, things suck harder. Think things suck because you’re a woman? Try being black, or disabled, or non-straight, or a trans woman. Things suck harder. This does not mean that things don’t suck for straight, white, able-bodied, cis women. But it does mean that for some women they suck even harder. This is not a difficult concept to wrap your head around if you have a minimum level of human empathy.

Now let’s go back to Suzanne Moore’s comment above: Intersectionality means that no one can speak for anyone else. Imagine the same comment being made by David Cameron; or Nick Clegg; or, frankly, any straight, white dude. Imagine a straight, white dude complaining that they weren’t allowed to speak for women, or people of colour, or gay people. Suzanne Moore would be the first on the barricades. That’s precisely what her original, unfortunately formulated essay that started all this is about.

When she complains about men legislating on women’s reproductive freedoms, she is objecting to others speaking for her. When she complains about certain parts of the left rallying around Julian Assange, she is objecting to others speaking for her. When she complains about David Cameron telling Angela Eagle to “calm down dear”, she is objecting to others speaking for her. What kind of cognitive failure does it take to write all that and then complain that intersectionality means she is not allowed to speak for other people?

There are some cases when it is appropriate to speak for others. They are few and far between, but they are there. They are those occasions when you have taken the time to truly listen and understand others. They are the occasions where your privilege – no matter how limited – gives you a voice more likely to be heard. They are the occasions when you can act as an ally.

Unless that is what you are trying to do – and you have truly taken the time to listen and understand – you are better off keeping your thoughts to yourself. And if, occasionally, you do slip up, then have the backbone to apologise and learn from the experience when called on it.